It's going to be hard to review Hannah Berry's Adamtine without spoilers, so I'll start with a tiny one to get us going: the crossword solution is "rhadamanthine"; the missing letters make up the book's title. That's not much of a spoiler, but it fills in a blank, a tiny detail. If you do know the word - and I had to look it up - it adds a layer, too. That's kind of the real spoiler: Adamtine is built up of these details and layers, and I'm going to talk about that. The plot has twists and reveals, and I'll try not to spoil them too much, but what really got me was how well the book is assembled to produce its effects.

Hopefully, me banging on about how well Adamtine creates atmosphere won't spoil it doing that for you, but if you think it might, go and buy it and read it first. Really, do.

You can download a preview from Hannah Berry's website.

It may actually take less time to read than this article. I loved Adamtine, and got a little carried away.

Enough gushing; let's talk about the unutterable. The book's title is the missing piece of a crossword puzzle its characters can't solve and are disoriented by. The most they can manage is "it's not Righteous", and the clue is later fed back to them by the narrative, posed to them over an abandoned intercom by what emerge to be themselves a few minutes in the future. Freaky, huh? It's a neat little microcosm of the story itself - something threatening and inscrutable pressing in on its participants with a grim ironic advantage.

Oh, and it has to do with the judgement of the dead. The word "rhadamanthine" derives from Rhadamanthus, a minor figure from Greek mythology, a king of Minos associated strongly with the rule of law and inflexible justice. In the afterlife he is a judge of departed souls. The resonance in Adamtine is clear, as something judges each of the characters, first handing them a note that accounts for all of their transgressions, and claiming them after the narrative has taken us back through the memories of their guilt. But taken with some of the story’s eerier impossibilities – the loop of space and time between the two carriages, the complete matt blackness outside, the spectre of Rodney Moon, it offers us perhaps a slightly different kind of ghost story.

Adamtine doesn’t commit to this, indeed, it doesn’t commit to many certainties, but we may be witnessing either these people’s disappearances from life, or just as well their transition and judgement as the dead.

Adamtine: a slippery abstraction of “uncompromisingly just”, something unknowable, and definitely “not righteous”. Cool, but what’s it about?

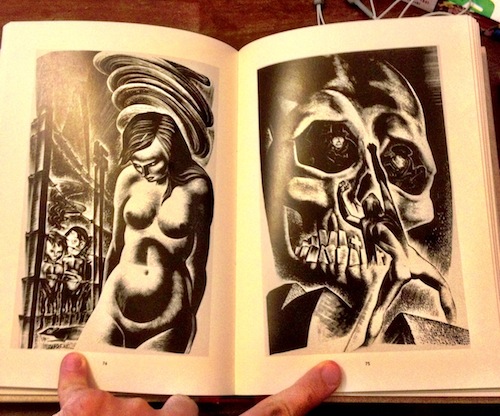

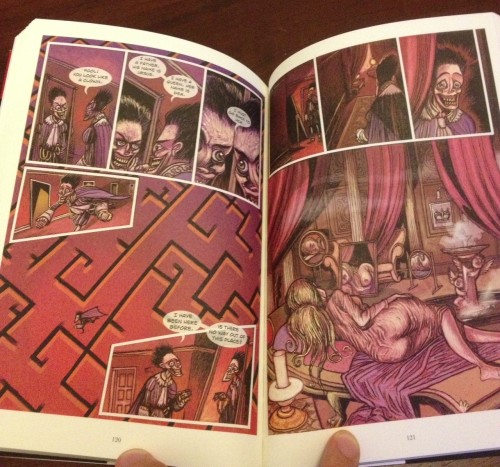

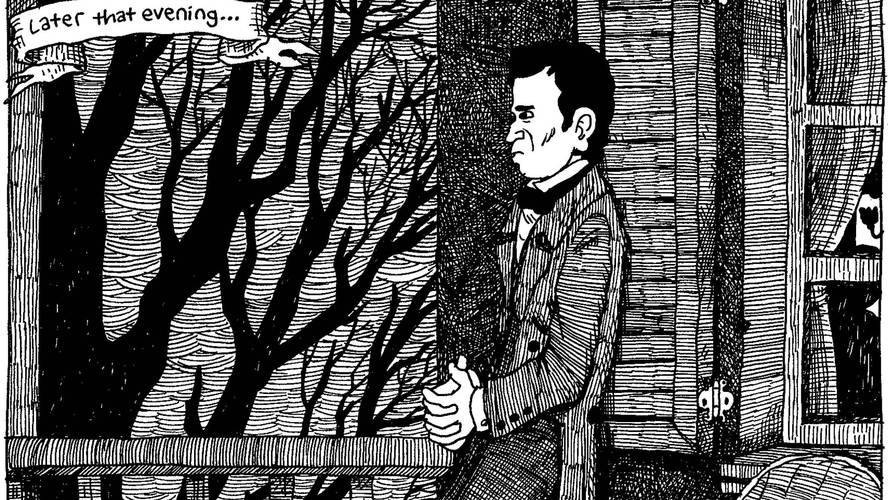

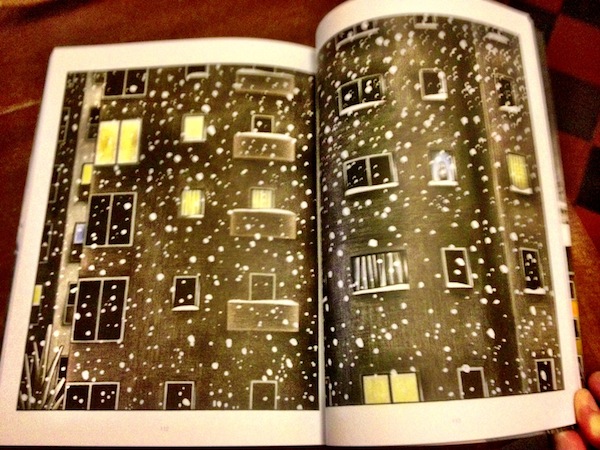

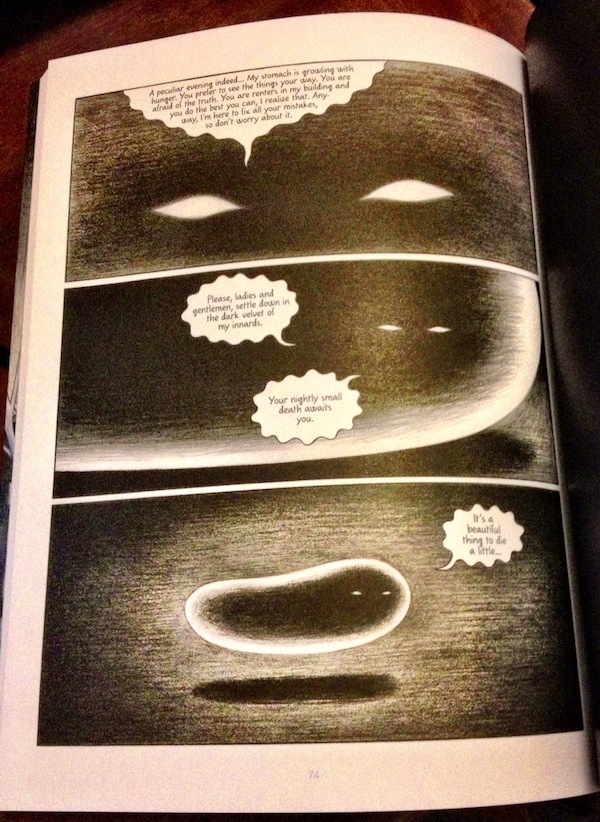

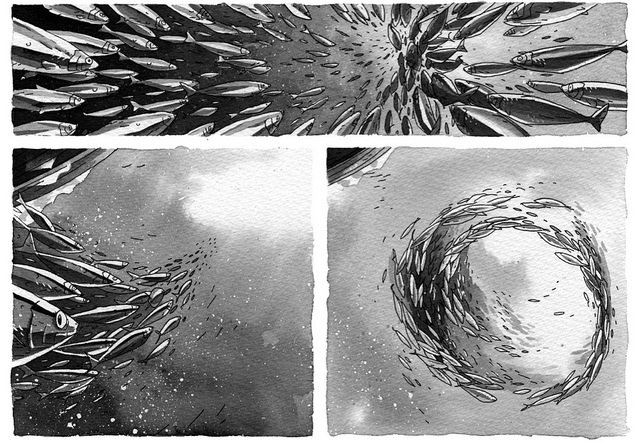

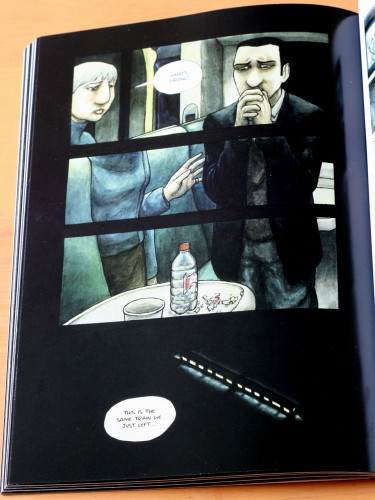

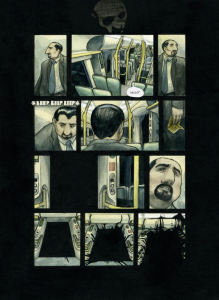

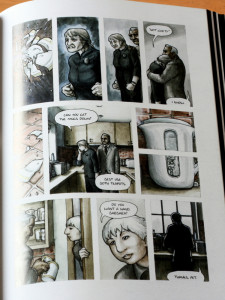

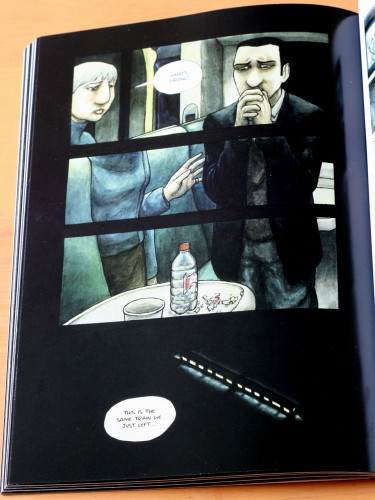

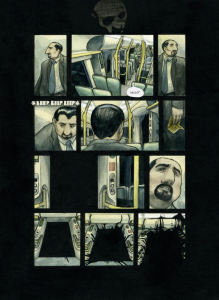

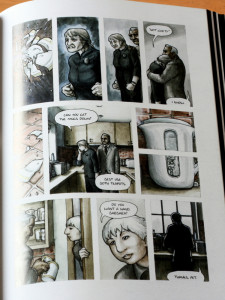

Four strangers are on the last train home. It is stopped in the countryside, decoupled from the other carriages, and it is pitch black outside. There is something in that darkness, and one by one, as their connections emerge, the characters begin to disappear. That's the basic structure of Adamtine. It's a pressure horror, a kind of Pitch Black for tired commuters with mysterious pasts. But this isn't a visceral horror of jump cuts, it's something more emergent and creeping. The thing in the darkness is the darkness - it's not distinct, and it seeps in from the pages' black gutters like running ink. It's a very immediate distortion of the characters’ present reality. The pages in the now have black backgrounds, the characters' recollections are white. The darkness pressing in is the boundary of the panels, the space outside the characters' knowable world. When it intrudes, coming for them, it decomposes the panels' hard edges and bleeds over their contents with flat black.

Four strangers are on the last train home. It is stopped in the countryside, decoupled from the other carriages, and it is pitch black outside. There is something in that darkness, and one by one, as their connections emerge, the characters begin to disappear. That's the basic structure of Adamtine. It's a pressure horror, a kind of Pitch Black for tired commuters with mysterious pasts. But this isn't a visceral horror of jump cuts, it's something more emergent and creeping. The thing in the darkness is the darkness - it's not distinct, and it seeps in from the pages' black gutters like running ink. It's a very immediate distortion of the characters’ present reality. The pages in the now have black backgrounds, the characters' recollections are white. The darkness pressing in is the boundary of the panels, the space outside the characters' knowable world. When it intrudes, coming for them, it decomposes the panels' hard edges and bleeds over their contents with flat black.

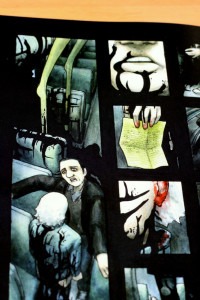

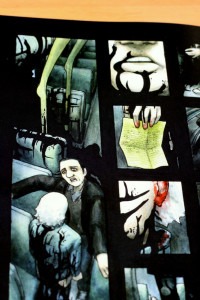

The bleeding is no accident - the shape of it suggests blood, and a lot of it. But there is no overt gore in this present. Those claimed by the dark simply vanish. Blood is reserved for the memories, for the past each of these characters contributed to. All of them played a small part in the death of a man: Rodney Moon, a serial murder suspect widely vilified. They find themselves now in a situation that reprises the circumstances of those murders.

Adamtine isn’t – overtly – an angry screed about justice in the court of public opinion, but it’s certainly set against that process playing out. Moon’s acquittal is deemed illegitimate by a public and media assured of his guilt. His defence is occult and implausible. Each of these characters believed him guilty such that they acted (or failed to act) in a way the ultimately lead to his murder. The moments we see of their pasts are largely the moments in which they decided his guilt, and the unacceptability of his innocence. Moon himself offers no comment. He has two words in the entire book. We never clearly see his face, and we are given no way to ourselves assess his innocence. Do we sympathise? Perhaps, but we must choose to. We perceive him only in terms of the thoughts of others. Even before his vengeful spectre haunts the train, he is an unknowable presence.

Uncertainty and unsettlement (indeed, Uncannyness) are a big deal in Adamtine. Two of the characters walk from one carriage to the next, a distance up the tracks, only to find that it is the same one and the objects they have discarded have reappeared. On their journey the dark presses in about them, and they’re drawn faintly, pallid. Their word bubbles are the clearest thing on the page, and as our eyes adjust to the contrast, and their conversation shifts around to their secrets, Moon’s abstracted face looms in from the gutters. You don’t necessarily even see it at first, or you half see it, uncertain as to what, quite, you've seen. It’s a beautiful piece of composition, and it’s part of the tracery of little details that hold Adamtine together.

Hannah Berry talks about this in a little detail in an interview with Forbidden Planet, discussing the ways in which detail builds horror. It’s well worth reading. In the same piece she makes the same remark she did at Thought Bubble – that there’s something especially torturous for an artist in setting something entirely on a train. The volume of finicky repetition must be exhausting, for sure, but it really pays off in those details.

For example: the train windows. They’re meticulously shaded to show reflections in the darkness; until they’re not. Windows, doors, any glass surfaces in Adamtine behave realistically with very few exceptions, and those exceptions are not errors. Nobody got lazy here. When the windows are matt black, it’s because they’re no longer looking out into the darkness. Whatever is coming has started to envelop the carriage and is moving towards its victim. It is as though the windows are looking out directly at the gutters, as though the situation is no longer quite real. This is telegraphed most strongly for the first disappearance – Moon’s face appears, the blackness occludes the landscape outside, a man limply holds a crabbed little note, aghast, a door opens onto nothing, and through it the ink bleeds in from the gutters; he vanishes.

For example: the train windows. They’re meticulously shaded to show reflections in the darkness; until they’re not. Windows, doors, any glass surfaces in Adamtine behave realistically with very few exceptions, and those exceptions are not errors. Nobody got lazy here. When the windows are matt black, it’s because they’re no longer looking out into the darkness. Whatever is coming has started to envelop the carriage and is moving towards its victim. It is as though the windows are looking out directly at the gutters, as though the situation is no longer quite real. This is telegraphed most strongly for the first disappearance – Moon’s face appears, the blackness occludes the landscape outside, a man limply holds a crabbed little note, aghast, a door opens onto nothing, and through it the ink bleeds in from the gutters; he vanishes.

It happens each time. Would it be glib to call it a kind of visual pun? To suggest that when there is no longer reflection, certainty has come for you? That may be a critical over-reach, but impulsive certainty and black and white morality are at issue here.

So: creeping details, a liberal dose of the Uncanny, impossible topology, a little Greek myth, and a complete evasion of certainties in discussing the consequence of impulsive certainty. That’s quite a laundry list for Adamtine. There’s plenty more going on in the book, for sure. I haven’t even mentioned characterization for instance. But the last one I’m going to poke about in is pacing an visual attention. It’s just brilliantly done.

Adamtine’s panels are by and large small. They often focus on a tiny detail of action: a hand on a cup, a shift in expression or posture. They slice time into tiny definite pieces, and in those slices move the flow of time very deliberately. To read Adamtine quickly is to do so inattentively – the composition demands a degree of lingering.

One of my favourite examples of this is a page that utterly decompresses a few seconds of domestic tragedy. It begins with a plate smashing, held, frozen by the image. It skips into bursts of emotion, and then slows right down. The plate shards are juxtaposed as a long panel next to a kitchen scene, and the sequence ends with a still closeup on a boiling kettle, itself split into two panels. This splitting of a single images recurs through Adamtine (and also Britten and Brülightly), either forcing us to linger on a detail as time passes around it, or superimposing the progression of narrative on something still and quiet. The panel division asks us to read the passage of time, the still image refuses, the eye almost bouncing off it. Plenty of cartoonists do this, but I've rarely seen it used quite so effectively to play with pace and attention as in Adamtine.

This technical excellence is not why you should read Adamtine – you should read it because it’s a brilliantly atmospheric horror story, well characterized, non-simplistic, and chock-full of great moments. But if you’re at all interested in how comics work then the way Adamtine is constructed is fascinating. Its use of detail and the emergent atmosphere are spectacular.