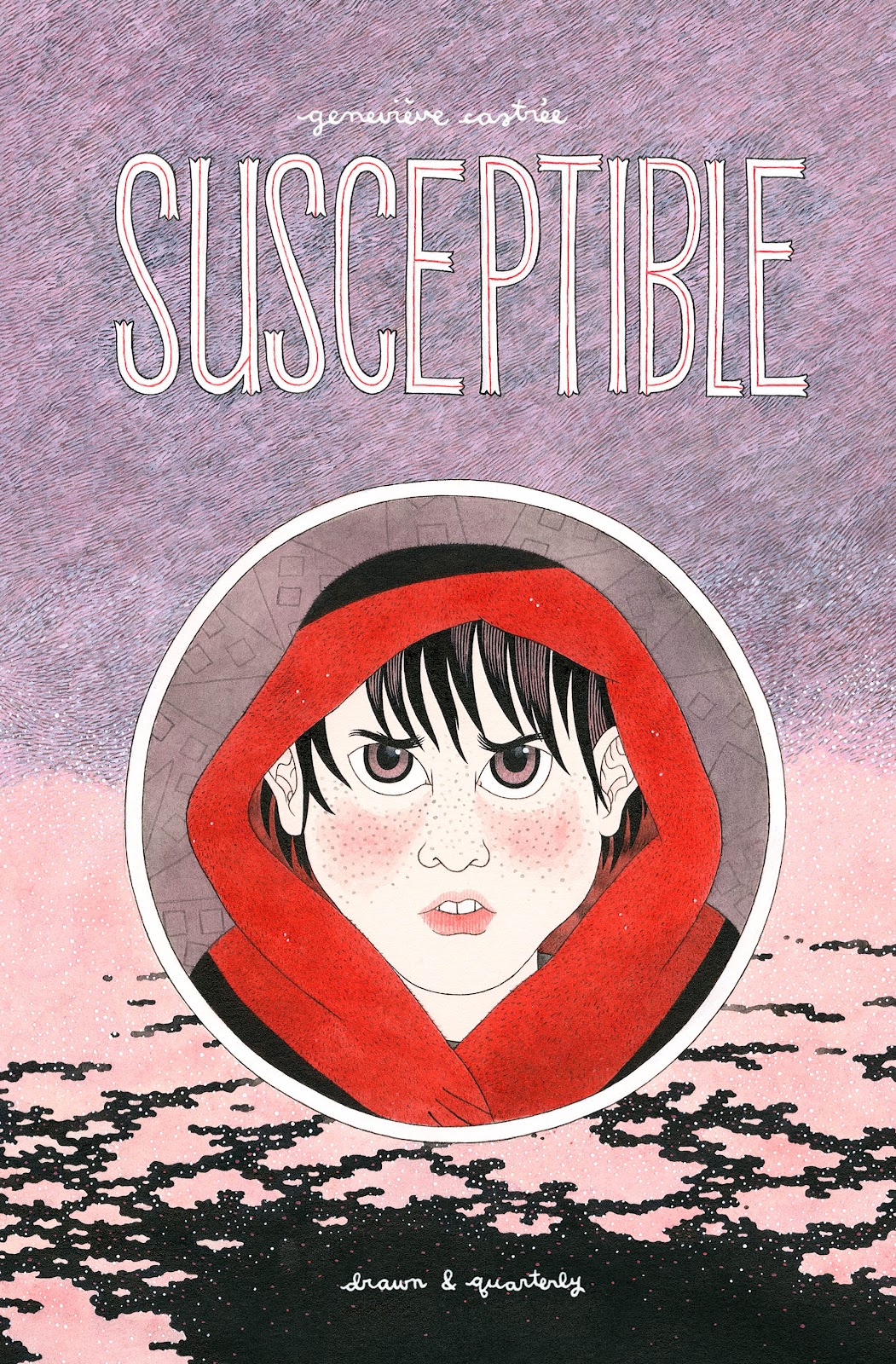

Geneviève Castrée's Susceptible (Drawn & Quarterly, 2012) is a coming-of-age comic (Bildungscomicheft?) about a young girl growing up in Quebec with a whole swathe of problems. At times, it's almost impossibly raw, bordering on painful to read.

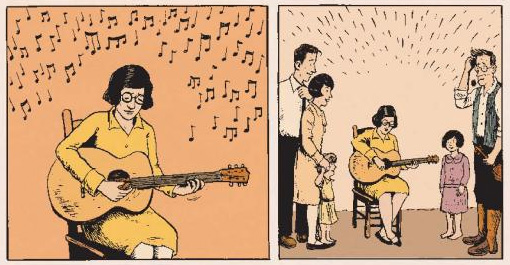

Susceptible treads the line between fiction and autobiography carefully (autobiography being impossible, apparently). The story is told from the perspective of Goglu (who, like the rest of the main characters, has a nickname for a name), but it's clear from the immediacy of the emotion drawn upon throughout that it is firmly rooted* in some version of Castrée's reality (past or present). And it's not a happy reality.

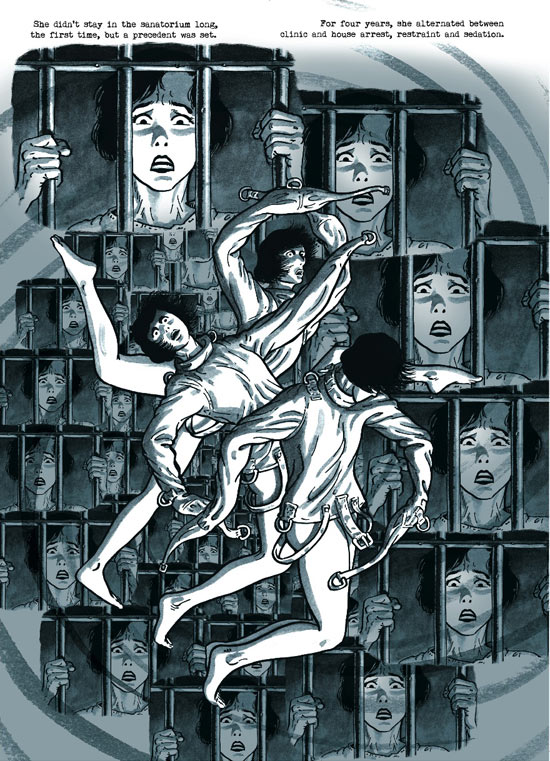

Unusually, for a comic on the subject of a troubled adolescence, very little mention is made throughout of the names society gives to the troubles common to this stage of life - depression, anxiety, eating disorders, etc. Rather than dwelling on these neat, medicalised categorisations of suffering, Castrée explores her protagonist's anguish as it is lived, not as it can easily be explained, and, in doing so, proves the limited utility of such categories as a lens through which to view human misery. The destructive, claustrophobic nature of the relationship between Goglu and her mother and stepfather, for example, builds throughout the book, and in doing so packs more of a punch than the few panels which touch upon her interactions with the medical establishment.

What I took away from this was a point well made about the experience vs the impression of suffering - the vast majority of art which focuses thematically on unhappy experience dwells on the expression more than the experience. And, whilst experience and expression may be inextricably linked, especially when it comes to something so fundamentally untangleable as one's early life (and art made out of those feelings, memories and years), Castrée successfully manages to focus on how Goglu feels, rather than the symptoms and expressions of those feelings. Which, in my experience, is a rare thing for a comic like this to do. And I liked it a lot.

Susceptible is not an easy read - it's painful and it's difficult, even with the moments of levity and humour that balance out the narrative - but I'd recommend it anyway. I guess this comes back to one of the reasons sad comics interest me - comics are often "easy", compared to prose or other media: they're frequently shorter, they tend to read faster, the narrative can flow more smoothly with the aid of visual cues and visual fluidity, and they're often light in tone as well as physicality. The point of sad comics is that they use the versatility of the medium to make something which isn't easy - something challenging, or confusing, troubling or (well,) sad. Susceptible is not an easy read, but great art isn't, always - and it's powerful and moving enough that I'm convinced of its merit in that regard.

*The opening pages show Goglu, becoming entangled in an ever-thickening patch of vines and leaves as she develops from a child into an adolescent, whilst the narrator describes the difficulty in picking apart how much sadness is innate and how much it's environmental. Metaphor drift, yo.