If you’ve ever had the nagging sensation you’re not getting something in comics, or you just want to know more about a broad and complex range of books, genres, characters and creators, you’re certainly not alone. Here to help is a list of the best books to help get to grips with all of the above. To make this list as broad as possible, I’ve mostly stayed away from books on creating comics - this will be a separate post further down the line. This will focus on comics theory, history, and some broad reference books. A list like this can never be comprehensive - if you think I’ve missed something, leave a comment or shout at us on Twitter.

Theory

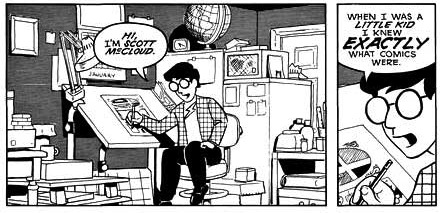

Understanding Comics

By Scott McCloud

If you want one book that covers as much comic theory as you could possibly need to get started, this is it. It’s presented as a comic itself with McCloud appearing as a guide-slash-lecturer, and covers art and literature theory, perception of space and time in comics, before trying to present a “unified theory of the language of comics”. This is the one book that will inform you the most on comics theory.

If you want one book that covers as much comic theory as you could possibly need to get started, this is it. It’s presented as a comic itself with McCloud appearing as a guide-slash-lecturer, and covers art and literature theory, perception of space and time in comics, before trying to present a “unified theory of the language of comics”. This is the one book that will inform you the most on comics theory.

Comics and Sequential Art

By Will Eisner

Before Scott McCloud had a go at it, the godfather of comics, Will Eisner, presented his theories on the comic as an artform. This focuses mostly on art and composition, but it’s fully accessible to non-artists. Eisner was one of the most consistently inventive comics artists of the 20th Century, and what he has to say here is worth reading.

Metamaus

By Art Spiegelman

Obviously recommended only if you’ve first read Maus, this is a hugely-detailed companion to the first graphic novel to get recognition outside of comics fandom. It’s full of the interviews, notes, and research that went into Maus - if you don’t mind making some of the connections for yourself, this is a great look at comic creation.

Obviously recommended only if you’ve first read Maus, this is a hugely-detailed companion to the first graphic novel to get recognition outside of comics fandom. It’s full of the interviews, notes, and research that went into Maus - if you don’t mind making some of the connections for yourself, this is a great look at comic creation.

Tintin and the Secret of Literature

By Tom McCarthy

This book takes a good stab at applying straight-up literary theory to Tintin, reading around the themes, Hergé’s biography, and global geopolitics at the time the books were being written. The result will appeal only to the degree that you can digest such rarefied efforts, but it’s a well-written and well-handled take on an analytical approach rarely applied to comics. English graduates may get more from it than the rest of us.

Supergods

By Grant Morrison

This is not pure theory - it’s a mixture of Grant Morrison’s life story and his thoughts on (mostly superhero) comics. Given his employment history, it naturally focuses mostly on DC, but Morrison has never shied from using superheroes as a canvas for grand, mythic, and frequently flat-out psychedelic tales, and he goes into this aspect of comics storytelling in a far broader sense than just covering his own work. He’s as mad as a sack of stoats, but he has plenty of interesting ideas.

History

Men of Tomorrow - Geeks, Gangsters and the Birth of the Comic Book

By Gerard Jones

The early comics industry was one of dirty deeds done dirt cheap, and that’s the focus of this book - the unlikely alliance of the earliest sci-fi fans and the hustlers of the 1930s that created the comic book industry. The prose isn’t dazzling, but it’s packed with anecdotes and is a robust history of the time.

The early comics industry was one of dirty deeds done dirt cheap, and that’s the focus of this book - the unlikely alliance of the earliest sci-fi fans and the hustlers of the 1930s that created the comic book industry. The prose isn’t dazzling, but it’s packed with anecdotes and is a robust history of the time.

Anyone who has read Michael Chabon’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay will recognise many of the anecdotes here, Chabon having borrowed them (from the original participants) for Joe and Sam’s story.

Marvel Comics - The Untold Story

By Sean Howe

A detailed history of Marvel from their inception as Timely Comics in the 1930s right up to the present day, Sean Howe’s book is a fascinating look at the personalities that shaped Marvel. Some of it is already well-known, but it’s all so well-told here as to be utterly compelling. It also features my favourite footnote of all time: “Blade was born in an English brothel and trained in hand-to-hand combat by a jazz trumpeter.”

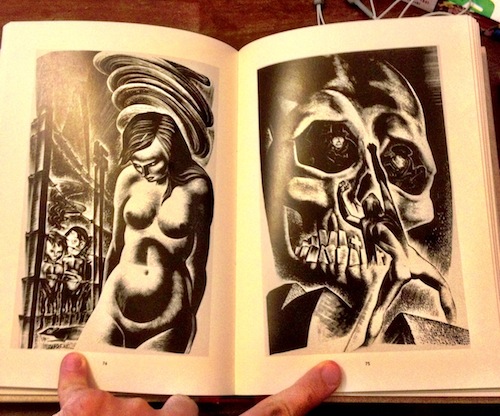

Wordless Books

By David A. Beronä

This is a bit niche, but in the early 20th century a small group of writers experimented with woodcut novels, similar to wordless comics. This book is an overview and history of the authors, as well as a showcase for some of the spectacular artwork.

This is a bit niche, but in the early 20th century a small group of writers experimented with woodcut novels, similar to wordless comics. This book is an overview and history of the authors, as well as a showcase for some of the spectacular artwork.

The Golden Age of DC Comics

By Paul Levitz

This is a puff piece, but what a puff piece. Produced by DC and art publisher Taschen, this is a giant, glossy hardback full of high-quality art from the Golden Age. Don’t expect balance, but it’s a glorious artefact. It is only the first of five planned volumes covering the history of DC though, so it could become a costly purchase.

Supermen! The First Wave of Comic Book Heroes 1936 - 1941

Edited by Greg Sadowski

Essentially, this is a collection of superhero tales from the guys who didn’t make it big. If you enjoy the strong pulp of the early days of comics, this is a good collection. There are some big names in the mix like Jack Cole, Will Eisner, and Siegel and Shuster, but mostly these are comics by the uncelebrated workhorses of the early funny book industry. A companion volume, I Shall Destroy All The Civilized Planets focuses on lunatic visionary Fletcher Hanks, who has one demented story in this volume.

Bat-Manga!

Art by Jiro Kuwata, Edited and curated by Chip Kidd, with Geoff Spear and Saul Ferris

The second title worthy of a self-appointed exclamation mark, Bat-Manga! is a collection of licensed Japanese Batman comics produced in the 60s by Jiro Kuwata based on the Adam West TV show. Author, designer and Batman scholar (a CV that suggests there is such a thing as a charmed life) Chip Kidd was already a collector of Japanese Bat-memorablia and comics when he decided to translate and publish the comics in English. The resulting collection is scattershot and frequently bizarre, but there are few books that are this much fun.

The second title worthy of a self-appointed exclamation mark, Bat-Manga! is a collection of licensed Japanese Batman comics produced in the 60s by Jiro Kuwata based on the Adam West TV show. Author, designer and Batman scholar (a CV that suggests there is such a thing as a charmed life) Chip Kidd was already a collector of Japanese Bat-memorablia and comics when he decided to translate and publish the comics in English. The resulting collection is scattershot and frequently bizarre, but there are few books that are this much fun.

Kirby - King of Comics!

By Mark Evanier

And again with the exclamations. If you’re a fan of Jack ‘King’ Kirby, this is a potted history of the man and his career, with some large-scale reproductions of his original linework. Unless IDW do a Jack Kirby Artist’s Edition, this is probably the best way to see his work in reproduction.

Reference

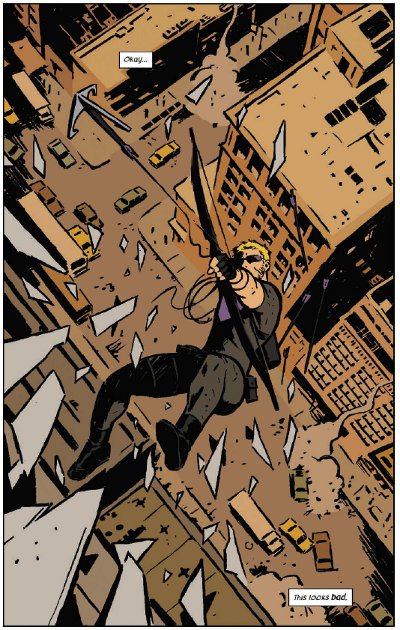

Reading Comics

By Douglas Wolk

This is the book that will give you a shopping list a mile long. The first third of the book is dedicated to a general overview of comics, while the latter two-thirds is a series of essays on notable creators, spanning a range from the oh-so-serious indie auteurs, to people like Gene Colan and Jim Starlin. While Wolk treats the subject seriously, the whole thing is filled with fan-ish enthusiasm, and it’s this that sticks. This book will make you read things you never would have considered before picking it up.

McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern Issue 13

Various authors, Edited by Chris Ware

For one thing, this is full of comics by great creators like Dan Clowes, Adrian Tomine, Chester Brown, and, as they say, many more. A lot of them are excerpts from then-upcoming books, all of which are now available. The more interesting stuff, though, is loaded at the front of the book - lots of historical nuggets like early sketches for Peanuts and Krazy Kat, a history of Rodolphe Topffer, the man who invented the comic form without really knowing it, and essays from very serious people like Ira Glass and John Updike.

For one thing, this is full of comics by great creators like Dan Clowes, Adrian Tomine, Chester Brown, and, as they say, many more. A lot of them are excerpts from then-upcoming books, all of which are now available. The more interesting stuff, though, is loaded at the front of the book - lots of historical nuggets like early sketches for Peanuts and Krazy Kat, a history of Rodolphe Topffer, the man who invented the comic form without really knowing it, and essays from very serious people like Ira Glass and John Updike.

1001 Comics You Must Read Before You Die

Edited by Paul Gravett

This is a really wide-reaching and well-researched book. Broadly split by era, it takes in the mainstream and indie US and UK comics (the primary audience seems to be assumed to be a UK reader), but it also covers a lot of manga and less-well-known European and South American comics. It’s another book that’s hard to flick through without coming away with a huge reading list.