David's first grandchild has just been born when he learns that he has terminal cancer. When David Lost His Voice, by Belgian comics artist Judith Vanistendael, is the story of David's last days, framed through the lens of his experiences and those of the women around him. This is sad comics fare on a number of levels: the English translation (from the original Dutch) is beautiful and poignant, the artwork is watercoloury and lovely, and cancer is definitely one of the sadder things to make comics about. Top five at the very least.

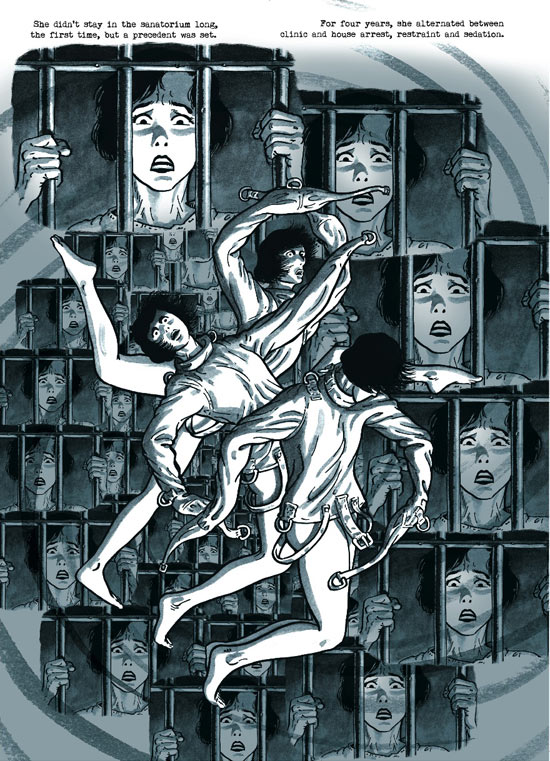

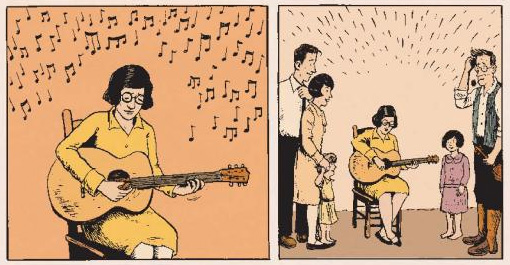

Vanistendael's art works within the visual idiom of comics - her characters are cartoony, and the majority of the narrative plays out within panels - but it also transcends the more traditional visual identity of the medium. Or, rather, the art of When David Lost His Voice seeps out beyond the edges of its own constraints. Vanistendael's arresting, vibrant use of colour is tempered by the fact that the book is entirely watercoloured, usually with incredible precision but increasingly chaotically as the narrative progresses. The paint spills over the linework in places, just as the art spills out of panels and onto single- and double-page spreads, breaking down structurally in parallel with David's body and becoming insubstantial with his flesh.

The imagery, too, is gorgeous. Morbid, certainly, but beautiful nonetheless. I'm a total sucker for a good danse macabre, and there's a two-page spread of perfect dancing skeletons to be enjoyed in one of the early sections of the book. Skeletons, unsurprisingly, are a strong visual theme throughout the commic. David's eldest daughter, Miriam, sees his skull staring back at her when she visits her father in his bookshop (I'm also a total sucker for the whole skull-through-the-skin thing). And the cover image of the English translation is of David's wife, Paula, lying in the foetal position next to a skeleton she has constructed out of chopped-up scans of her husband's metastases. It's a very subtle birth/death parallel, and one which echoes the same theme within the narrative - the Dutch cover, interestingly, is somewhat more explicit and less allusive in this regard - and it works.

The narrative is split into five parts. The first and last sections are David's story, whilst the middle three depict the experiences of Miriam, his adult daughter, who has just given birth to her first child, Paula, his young second wife, and Tamar, the eight-year-old daughter of their marriage. Each of the sections is prefaced with a few lines of poetry - something which often doesn't work, but in this case absolutely does. It is very much a story of people not talking about things: Paula is frequently frustrated by her husband's reluctance and failure to communicate with her, and Miriam is hurt when her father waits months before mentioning his diagnosis to her. This theme is more profoundly realised when David's larynx is removed to allow him to breathe more easily - after keeping so much to himself for so long, he has been forcibly silenced, and it is only then (through handwritten notes) that he is finally able to express to Paula in words what he admits he has never been able to say: that he loves her.

However, the book's silences represent more than frustration. After spending his last holiday alone with Tamar doing things intended to delight her, David puts his young daughter to bed, goes out to the back of the houseboat they're sailing around a lake on and smokes a cigarette alone in the dark. It's a powerful scene, and evokes something which would be more or less impossible to do with words.

The words, though, are also incredible in their simplicity. There's something haunting about an eight-year-old child crying out to her father, "Please Daddy, don't die."

When David Lost His Voice is one of the saddest of the sad comics, but there's hope in tragedy - a single robin seen from the window of the hospital canteen while Paula and Tamar hide from the man they love as he dies - and redemption and love in the the final days of David's life, and in his death. It's a thing of splendid, moving beauty, and you should absolutely check it out.