Artist: Mark Stafford

Artist: Mark Stafford

Writer: David Hine, adapting Victor Hugo

Any mention of The Man Who Laughs, especially in relation to comics, must start with the fact that the story’s protagonist, the disfigured orphan Gwynplaine, inspired Batman’s nemesis The Joker. With that legal requirement out of the way, let’s look at this graphic novel adaptation of Victor Hugo’s novel. David Hine (writer of the bizarre and brilliant Bulletproof Coffin) has adapted Victor Hugo’s rambling tale of class, nobility (the other sort) and betrayal into a lean graphic novel. Mark Stafford’s art is the main draw, creating a world populated with angular, sickly-looking people and stark landscapes. There are sections that look like woodcuts, and some genuinely astounding layouts. The sickly candlelight that bathes the characters gives a gothic feel to the proceedings that arguably doesn’t exist in the novels, but it’s so stylish and feels so appropriate to this telling that it’s hard to complain.

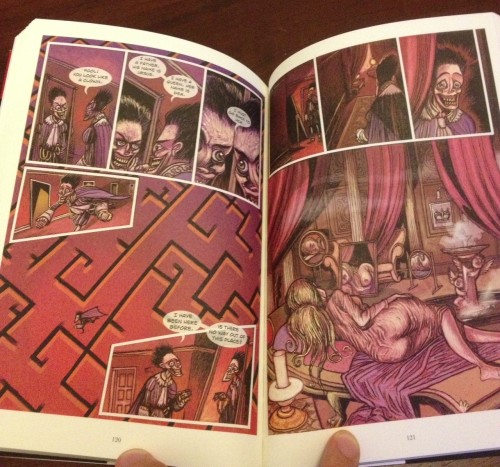

David Hine (writer of the bizarre and brilliant Bulletproof Coffin) has adapted Victor Hugo’s rambling tale of class, nobility (the other sort) and betrayal into a lean graphic novel. Mark Stafford’s art is the main draw, creating a world populated with angular, sickly-looking people and stark landscapes. There are sections that look like woodcuts, and some genuinely astounding layouts. The sickly candlelight that bathes the characters gives a gothic feel to the proceedings that arguably doesn’t exist in the novels, but it’s so stylish and feels so appropriate to this telling that it’s hard to complain.

If there’s one criticism to be leveled, it’s that the production can occasionally look a little too digital. Hand-drawn lettering would definitely suit the art style more, and the colouring is occasionally a bit rough - there are some panels where the digital brushwork stands out to a distracting degree. These are minor concerns - the artwork is mostly superb.

The story is akin to the Good Bits Edition in the novel version of The Princess Bride - it makes for a far more readable take on the story. What it loses though, is the constant wry yet furious presence of Hugo in the prose. The book was written while Hugo was in exile in Jersey for his republican beliefs, and his distaste for the class system and the upper classes in general drips venom from the pages. Some of that is present in this adaptation - “The people rejoiced. In the time of Cromwell, speech was free, the press was free. England had been in a dream. Where should we be if every citizen had his rights? Was ever anything so mad? What joy to be quit of such errors!” - but what the story gains in brevity it definitely loses in the absence of some of the ripest prose. Still, this is a strong adaptation that makes some bold and vital choices that were definitely needed to succeed as a graphic novel. It's probably better for those who've already read it as a novel, but it works in its own right.