Good news, everyone! Comics aren't just for kids any more! I know we've been saying this for a while - about Watchmen, about Fun Home, about Maus - but we really mean it this time. Adults of impeccable taste who enjoy really good books, as long as they're reliably proven to be literature by the judges of major literary prizes sponsored by famous coffee chains, are finally allowed to read stuff that comes with pictures as well as text. Huzzah! Now, I don't begrudge Dotter of her Father's Eyes its success. I don't begrudge it anything, in fact, because it's splendid. It combines two of my favourite ographies, biography and autobiography, and does so with aplomb. If you're not familiar with Mary Talbot's work on critical discourse analysis, or Bryan Talbot's stint at 2000AD in the eighties and/or taste in bad puns, there's no need to worry. Even if you weren't lucky enough (as at least two thirds of the ConSequential team were) to see Bryan bumming a smoke off someone outside the main hall at Thought Bubble this year, you've got nothing to worry about with Dotter. It's both charming and accessible. Maybe that's why fancy people love it so much.

I should confess at this point that I, too, am fancy people.

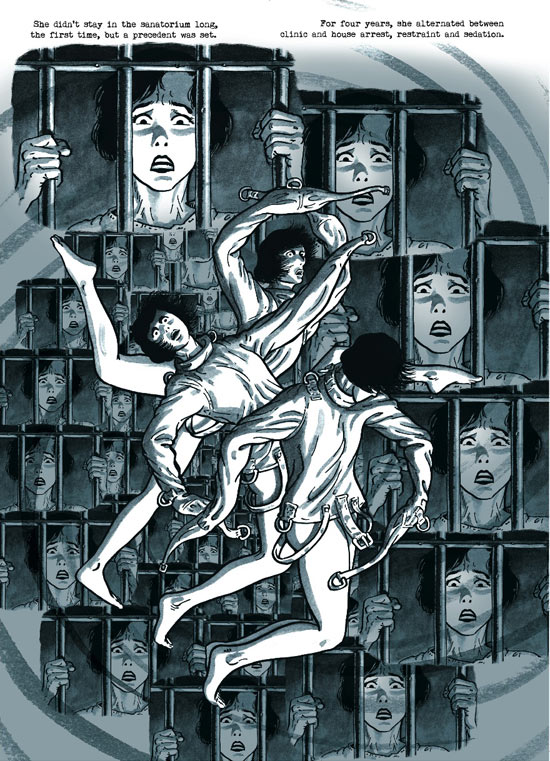

Fans of Asterios Polyp will enjoy the fact that the Talbots use no fewer than three different art styles to delineate the boundaries between their present (or near past), their past and the life of Lucia Joyce - bold colours and strong linework for the present, pencil and sparse/muted colour for Mary's youth and a gorgeous palette of dark blues, greys and blacks for Lucia's story. The panels depicting the end of Lucia's life are particularly powerful.

The sections dealing with Lucia Joyce are excellent both in terms of their emotional impact and in the storytelling, dialogue and sheer vivacity of character that they portray, but no good scholar of critical discourse would let us get away with a simple biography. The details and events of Lucia Joyce's life are used to draw parallels between and associations with Mary Talbot's childhood and youth, and it's very much Mary's story, rather than Lucia's, which really steals the show. It's even Mary who crops up on the cover, which almost certainly means something about something.

The two histories in question complement one another well: they're tales which share common themes and threads, but by no means the same outcome. The last years of Lucia Joyce were not happy ones, whereas Bryan and Mary, in spite of their circumstances and setbacks, seem to be doing more or less all right (they've just won a Costa prize, for one thing). And perhaps it's this which makes me feel that their story is more central to Dotter than Lucia's. The life of Lucia Joyce, if treated as a straight biography, would be as sad as the saddest of sad comics. But when similar themes and experiences from Mary's youth are highlighted, and comparisons invited, there's a sense of triumph and a very real glimmer of hope. Lucia could not right the wrongs of the past, but the Talbots may well have managed to achieve that.

In terms of sad comics specifically, there's a lot here for fans of the genre: class issues, daddy issues (both Mary's and Lucia's), thwarted hopes and dreams, parental pressure, incarceration, people doing bad stuff to ladies (at least in part simply because they happen to be ladies at a time when that wasn't necessarily a good thing), living in Wigan, getting knocked up and subsequently married really young because that's the thing to do, and plenty more. Some solid sad comics fare for those of you who enjoy a really sad comic.

I hope that people will read Dotter because it's a fantastic comic, and not just because it's fantastic and also happens to be a comic. I haven't said a lot about panel structure, but the three distinct art styles do interesting things within the medium, and it would be nice to hear some more about that and a bit less about how it's safe to come out of the comics closet now that the middle classes have been reassured (which brings us gently back to class issues. Boom.).

If this hasn't been enough to make you want to go and read Dotter, I'd like to close by quoting James Joyce himself (as Mary Talbot quotes him in the book): "It's enough if a woman can write a letter and carry an umbrella gracefully."

If nothing else, Dotter proves Joyce to be as much of a jerk as that quotation suggests. Enjoy!