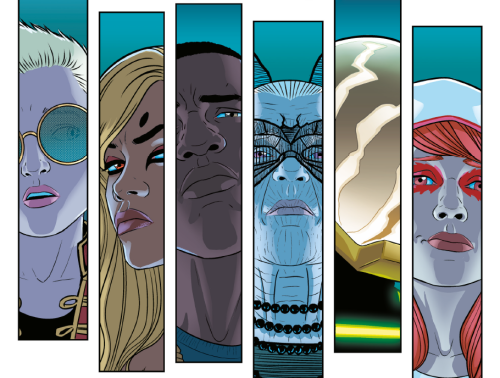

By now, all 13 of the gods of the latest recurrence have been revealed (yes, we'll get to that), as well as a few extras from past cycles. So we're overdue for an update.

Spoilers? Damn straight, spoilers.

We covered previously revealed gods: Lucifer, Baal, Woden, Amaterasu, Sakhmet, Morrigan, Baphomet, Minerva, Innana, Tara, Ananke, and Susanoo (1923) in an earlier post.

This is loosely based on WicDiv #1-28 and the 1831 stand-alone story Modern Romance (eighteen-thirty-oneshot?).

So, who's who who's new?

Dionysus

The dancefloor that walks like a man. Bacchus to the Romans, he's easy to think of as a jolly, tubby party god. Dionysus is god of wine and grape harvest, drama, ritual madness, and springtime fertility. But WicDiv didn't pick comedy Bacchus. This is a younger, leaner Dionysus, something more like the ephebic trickster of Greek drama.

His emblem is a grape bunch of little pills, and he looks like an archetypal raver kiddie. Gillen, naturally, points us to Spaced.

Cults of Dionysus have appeared on and off at least as far back as the pre-Greek Minoan period (about 2000 bc), and his worship has a consistent element of mystery and the ecstatic.

Dionysiac mysteries (the practice of his cults) blended dance, frenzy, drugs, booze and trance states in their worship. There was an outsider element, too - sexual and social transgression, and a hint of danger.

In Euripides' The Bacchae, Dionysus (a young god, with human relatives) is decried by Pentheus, ruler of Thebes - and his cousin - as both a fraud and a public menace. His response doesn't do much to address the latter: he initiates the women of the town into the ranks of his most hardcore followers, the Maenads, and in their frenzy they tear Pentheus apart with their bare hands. Imagine cleaning up after that party.

In Euripides' The Bacchae, Dionysus (a young god, with human relatives) is decried by Pentheus, ruler of Thebes - and his cousin - as both a fraud and a public menace. His response doesn't do much to address the latter: he initiates the women of the town into the ranks of his most hardcore followers, the Maenads, and in their frenzy they tear Pentheus apart with their bare hands. Imagine cleaning up after that party.

In WicDiv, Dionysus is a good guy(ish) with something moving under the surface. Laura calls him "the best of them" and he does not leap to agree. Self-proclaimed as a lover not a fighter, he tries to keep his hivemind safe in #21's face-off at Valhalla. But he mucks in with Amaterasu's cult and Woden's experiments, and it's worth remembering he's a god with strong underworld associations. Mythically, one who visits the underworld, and one of few that have brought souls back.

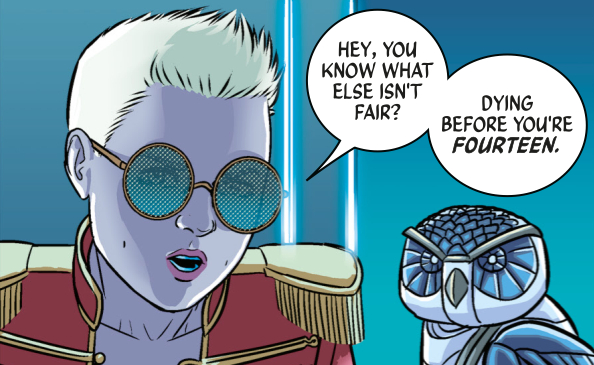

So far, The Wicked and the Divine has shown us a Dionysus with an undercurrent of danger, rather than full-blown bloody bacchanal. He pops his signature Thyrsus staff as neon nunchaku at Valhalla, but we don't see it elsewhere.

In Greek tragedy, the Dionysiac is often set in opposition to the Apolline. That is to say - kind of - chaos vs order. They're different takes on the ideal of kouros - smokin' hot muscle twinks, basically; one side all Preppy College Boy, the other all Scuzzy Sk8r Boi. Apollo is prophecy, fate, and structure. Dionysus is more free-for-all: emotive and chaotic. The impulses frequently clash in Greek literature, and it's picked up in Hegel and Nietzsche's respective takes on tragic theory.

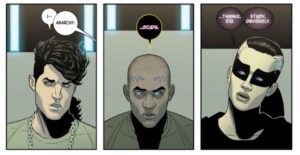

Interesting then, that Gillen and McKelvie's Dionysus, while emotive and ecstatic, feels far less chaotic, even explicitly choosing study over anarchy in #26

Interesting then, that Gillen and McKelvie's Dionysus, while emotive and ecstatic, feels far less chaotic, even explicitly choosing study over anarchy in #26

Also conspicuously absent: relentless penises.

Dionysus is a dick god. Not like Woden. Like, he's just all about the dicks. They're his symbol, and they're everywhere in his representations. Some of his followers would wear giant strap-ons in religious ceremonies and processions. Bring that one back, I say - really spice up the church fete.

Urdr & The Norns

Like Baphomet and Lucifer, The Norns are in the not-quite-gods camp. Imagine the Greco-Roman fates, but Norse. They're three (usually) powerful giants who sit at the foot of the world-tree Yggdrasil, keeping it watered from the well of Uror.

Seen as law makers and arbiters of fate, one reading which might be particularly interesting for WicDiv is that they set the length (as well as course) of mortal lives.

In this recurrence, their symbol is Yggdrasil, and it's deliciously fitting that Urdr should be Cassandra. Prophetic gods are a nice echo for her name, as is their journalistic investigation of the pantheon.

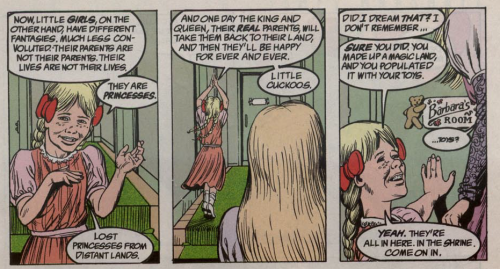

Unlike Amaterasu, Lucifer, and especially Woden, Cass attempts to keep her name, rather than leaning on "Urdr". She's cast by the others as the token grown-up, and is, frankly, done with their nonsense. She gest some of the very finest "what is this fresh crap" reaction beats:

There's a lot of really interesting identity stuff cohered around Cassandra/Urdr. It's dissected brief in her fight with Woden over his cheap crack about their apotheosis and previous identities, versus her transition. Her discomfort at having to perform the role of Urdr is palpable, as is her discomfort at the crowds just not getting it.

A skeptic become a god, with the name of a disbelieved prophet, disbelieved in turn when she tries to tell the world there are no gods and there is no prophecy. Tough gig.

In the Snorri Sturluson version of Norse myth (a 13th century monastic compilation of the old tales) there are many Norns, drawn from many races. In particular, from men, dwarves, and elves. This may give us the visual touchstone for Verdani and Skuld - one willowy, one shorter and broader.

She was the last good to be "found" by Ananke, or at least so we thought until we met...

Persephone

Issue 11: exploded head on the cover, 12 gods revealed, "It's going to be ok" on the flyleaf. Boom. Laura is Persephone. Persephone is dead. Grab a pomegranate and strap in.

Persephone's pretty well known as a concept: a stolen celestial daughter, spending half (sometimes a third of) her year in the underworld, her absence/return signifying the transition of winter into spring.

She's also deeply entangled with one of classical Greek religion's oldest mystery cults, and has back-story continuity arguments that make Madelyne Pryor look like some weaksauce Spot's First Walk intelligibility.

Persephone was a daughter of Demeter, goddess of harvest and agriculture. She was abducted by Hades, ruler of the underworld. In searching for her, Demeter created a great drought and famine, pressuring Zeus to intercede, and leading to hades granting Persephone's return. As ever with these wily deific bastards, there was a catch.

Persephone didn't read the fine print before snacking down on a juicy pomegranate, and having eaten the food of the underworld, she was bound to remain there. In this case, for one month for each seed eaten (4 or 6, depending on who you believe).

So far, so harvest myth. But it does get wibbly.

Four months of Persephone in Hell just about gets you the drought of a Greek summer. But her return rites are celebrated at the beginning of spring, as part of a rebirth/fertility cycle. The Eleusinian cult probably grafted together Persephone with earlier Minoan harvest goddesses, Demeter with ur mother figures. Other mystic takes on Persephone mix in the nature goddess Kore, so it gets kinda mangled.

Above ground, Persephone is all vegetation and plenty, and a bit better know. But her role in the underworld shouldn't be downplayed. She ain't sitting around down there.

As queen of the underworld, Persephone is probably fused with the older, weirder figure of Despoina. Think: birth, death, and a whole load of must-be-appeased nature worship. In her cult it was forbidden for the uninitiated to speak her name, a tradition that clung to the chthonic Persephone. She presides over the dead, and in the tradition of Orpheus, metes out judgement.

As queen of the underworld, Persephone is probably fused with the older, weirder figure of Despoina. Think: birth, death, and a whole load of must-be-appeased nature worship. In her cult it was forbidden for the uninitiated to speak her name, a tradition that clung to the chthonic Persephone. She presides over the dead, and in the tradition of Orpheus, metes out judgement.

WicDiv picks this up heavily, in particular associating her with the idea of "the destroyer", which is one possible etymology of her name. Her nascent cult, too, won't name her. She likes it. She has root and vine powers, is potentially stronger than the other gods, can drag people down to the underworld, and shows this dual aspect with her flashes of skulls-for-pupils.

In #11 she apparently dies. In #18, she's back. In a basement dive bar, of course. We later find out that she spend months hanging out in the underworld with Baphomet. Moping, fucking, planning.

A lot gets hinted at. Ananke expected her back, but no so soon, and her status is debated by the remains of the pantheon. In a millennia-spanning set of ninety year cycles of renewal, it seems unlikely that a Persephone figure - heretofore hidden - has no significant role to play.

Nergal (Baphomet)

We spilled some ink last time on godhood as identity performance in WicDiv, and shit just got recursive. Baphomet comes from recent-ish demonology, and only get the goaty horn business in the 1800s. There's something fishy about him as one of the WicDiv gods (we covered this in part 1) and he certainly seems twitchy.

In the underground with Persephone, Baphomet tells us his origin story as... Nergal?

No, me either, a bad rendition in the Hellboy movie notwithstanding.

He's... Baphomet with lion bits? Certainly explains the teeth. Except emblematically it should probably be a fighting cock, and - look the whole thing's a joke about nobody knowing who Nergal is, and Baphomet still having to LARP as a god, even post ascension to actual godhood.

But that doesn't mean it isn't interesting.

Nergal is a Sumerian/Mesopotamian figure, and so could go back a couple thousand years BC. There's a nice irony there with Baphomet being a relatively modern invention. There are plague associations, and he's depicted variously as a lion or a chicken. In this case, a string of "raging cock" jokes seem appropriate.

Nergal's a sun god (with war aspects) who became an underworld god, perhaps via a sunset association. This makes him a fire god of the underworld, and you can picture the character as written scrabbling around for a fit before coming up with Baphomet, probably via early Christian mystics and demonology.

The figure was co-opted there as a demon, perhaps by 18th century occultist.

Niche.

Hades (1831)

On the one hand (ahem) it's a two-page appearance in a one-shot side story. On the other, it is a new god, so here's the quick version.

Hades is king of the underworld in Greek mythology, and here represented as John Keats, the original teen emo poet.

In his writers notes, Kieron Gillen hangs this off Keats' poem This Living Hand:

This living hand, now warm and capable

Of earnest grasping, would, if it were cold

And in the icy silence of the tomb,

So haunt thy days and chill thy dreaming nights

That thou wouldst wish thine own heart dry of blood

So in my veins red life might stream again,

And thou be conscience-calmed — see here it is—

I hold it towards you.

That's pretty on-brand for Keats. Check out Ode to a Nightingale one of his better-known bits of gothing about.

It's easy to mock Keats for what feels like melodrama, and if I had another couple hundred words to spare, I would. But his work is also gorgeously sensual, with a real ear for rhythm and cadence. The morbidity is fascinated, dream-like. Through all of its florid verbal garishness, there's something to Keats that I resent myself for responding to.

We don't get much of him in the 1831 special. As with his factual counterpart, Hades here dies in Rome. Keats of tuberculosis, Hades, of Ananke sticking a knife in his heart.

Mythically, Hades was both the god and the realm. The land of the dead and its ruler. Not a satanic figure, and not presiding over a hell, per-se. Hades officiated more than he tormented, and was never quite a tempter or a figure of evil. As a Death figure he is implacable, and like Persephone it could be taboo to name him.

In The Wicked and the Divine Hades' main role is to get his hand cut off, which is then used by Lucifer to create a necromantic golem on the shores of Lake Geneva. We have very little sense of him, but it may be salient that at least some of Hades is potentially still out there, and in a universe that contains an unexpected return of Persephone.

...and bonus Pink Woden?

Totes the monster from the 1831 story, right? (The eighteen-thirty-onester). Well, maybe. What could you make from the hand of Hades, a squeeze of Morrigan and Lucifer, and a heaping tablespoon of Woden?

"Pink Woden" is briefly glimpsed in #14, as part of the remix issue's original art parenthesis. Woden is talking to someone, and with what could even be earnestness or affection. A Valkyrie he actually likes? Someone to monologue to? Or something more complex entirely?

Now, a couple of the other gods have multiple aspects, some maybe everyone's favourite neon MRA dickhead is only part - or rather half - of the story. If Nergal can call himself Baphomet, and given Ananke explicitly calls Green Wooden "the pet of a god" in #14, well, might we not wonder about Huginn and Muninn (Knowlwedge and Memory, Odin's raven spies/pets)? Or Geri and Freki (similar, more bitey, wolves), if thought and memory have a bit too much finesse for the character as seen?

Some fan theories say Pink Woden is Laura's sister. I could buy that for the emotional punch, but it would lack the mythic heft. I absolutely cannot buy that the 1831 monster is a thread that won't be picked up again, either. Throw in the colours, and my money's on the monster.

But I wouldn't bet against wolves or ravens. If we fancy getting proper twitchy, well, there's Baphomet's "idea golems", introduced just before we find out about Woden's dead mother, and as he talk about reverse-engineering the other gods' powers. Pink Woden, in the tiny glimpse we have, is not unlike one of the Valkyries, and dead-mum simulacrum would be weirdly on-brand for both Woden as presented, and a comic that's so knowingly post-Buffy.

If it is the eighteen-thirty-onester (not sorry), there's a lot of quite exciting fanwank on the table. The best way to ensure Lucifer would do a thing was pretty much to warn him not to, and then give him the bits, so we can be pretty sure than Ananke was at least basically cool with the monster's creation. We know she's lonely, we know she talked to Robert Graves, and we know she's writing to someone at the end of #28. Someone colour coded with pink sparkles, perhaps?

Enough speculation. Whaddya reckon - mummy, monster, magic raven?