One of the big themes of The Wicked and the Divine at this point is performative identity. The gods are a big part of this - they are the person they were before they joined the pantheon, a pop star, and an existing god. What that means though is not clear - and many of the gods take on more than one form.

Our most recent podcast talks about WicDiv, and in what's a bit of a mammoth post, we've looked at the gods' background, who they are, who they were, what they do, and some of what it might mean.

Dave gets his myth on, and Roger talks performance...

(This post covers roughly issues #1-7. The rest of the gods are covered in part 2 here.)

It’s worth noting that there are no fixed versions of any of these gods - it is the nature of mythology to be mercurial (ho-ho!). In reading about mythology, it is useful to think of gods not as a fixed point or a character. Gods and stories move from one region to another, take on new character as stories are retold, embellished or deliberately changed. For example, Woden is a later form of the Teutonic war god Wotan, eventually becoming the familiar Odin of Norse mythology. One version does not replace another though - geography and means of communication in early cultures mean that there’s not much by way of canon. Woden and Odin are not exactly distinct, they are points on a scale.

The myths that we understand today have come from oral sources, and only certain versions have been written down. Different mythologies are better-known than others. Roman and Greek mythologies are comparatively well-recorded, for example, whereas Norse and Irish myths come from only a few written sources. Conquering cultures add their own spin - much of Norse myth comes from a book called the Prose Edda, written by Snorri Sturluson was written from a Christian perspective, and deliberately mocks the beliefs of earlier generations - almost certainly showing off the author’s devotion to the new religion of his land.

What this is then, is a brief series of notes on each of the gods revealed so far, an explanation of the texts and traditions they’re derived from where appropriate, and an attempt to reconcile that with The Wicked and the Divine. Bear in mind as well that the nature of the comic allows for swathes of this to be altered or ignored - it is hardly a straight-up take on the classic myths. This guide goes as far as Issue 6, so potential spoilers up to that point. It doesn’t cover anything beyond that, so there’s nothing for the final god, even though he’s out in the wild now. This guide also focuses on the comic alone - no interviews or text notes have been taken into account. Old school. Shall we?

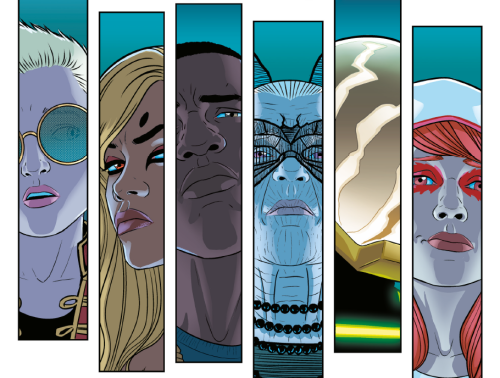

The Gods

Ananke

Ananke comes from Greek mythology and pre-dates the gods in the same way as the titans do - she is a force outside of gods and mortals, and her name means “force, constraint or necessity. She is sometimes depicted as the mother of the fates, and she is often depicted as holding a spindle, with which she weaves the fate of all beings. In The Wicked and the Divine, she is the only member of the pantheon that doesn’t have a pop star aspect, and she is always (so far) depicted as being both old and the same person. Given the focus on identity and performance for all other characters, this seems worth considering. She is almost certainly playing at least one role that is not currently obvious.

Lucifer

Lucifer isn’t usually thought of as a god in the strictest sense - those pesky monotheistic religions really do like to stick with just the one - but he definitely has the characteristics of one. The usual symbols associated with Lucifer are fire, snakes, goats, horns in general - the usual horrow show. The Wicked and the Divine emphasises Lucifer’s angelic origins, with the white suit, and the occasional feather motifs. Dark stripes and eyes that flare red when she uses her powers are the only outwardly “satanic” traits - this Lucifer seems to be primarily in it for the spirit of rebellion and the opportunities for temptation. Baphomet seems to fill the role of the Halloween horror satan in The Wicked and the Divine’s pantheon.

If this is what Lucifer is in The Wicked and the Divine, then she represents rejection of authority (though curiously not Ananke’s - she seems to be faintly awed by her), open rebellion and temptation. She flaunts authority at every turn, often in an aggressively sexual way. That seems to cover that.

The name on her gravestone is Eleanor Rigby, but this is likely just to hide the grave site from fans, although going by the shortened “Luci” could be a Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds reference. These aren’t her parents’ bands - they seem to prefer “some awful Britpop covers band”, so it seems to be another small act of rebellion. The main touchstone for her appearance is “Thin White Duke”-era David Bowie.

Baal

Baal can refer to a number of gods from the Middle East that are roughly contemporary to the Old Testament - Baal (meaning “Lord”) in most cases refers to the god of the Canaanite tribes around Carthange (known as Baal-Hamon), and the Baal-Hadad version that appears in The Wicked and the Divine is the god of the Phoenicians - a people who are believed to have originated from the Canaanites. This is the first hint of how The Wicked and the Divine is handling how different interpretations of the same god are represented in the pantheon - Baal is aware of his nature, and each time he incarnates he may be a different aspect of the same god.

Baal-Hadad is a lightning and rain god, representing fertility. His Wicked and the Divine incarnation is broadly modeled on Kanye West, is furiously egotistical, and is playing up to his designation as “lord of all”.

It is believed that the term Beelzebub is derived from Baal-Zabab, or “Lord of the Flies” and that the Israelites justified the destruction of the Canaanites by labeling them as satan-worshippers. They are referred to as having been wiped out in the Old Testament. Baal represents some of the more interesting possibilities for the Wicked and the Divine to play with how the gods manifest - what defines the versions that appear as a unique aspect in different Recurrences, how they are defined as separate, what humans factors play a part in that. Unless it was a throwaway line, in which case I’ve gone off on one for no good reason. Carry on.

Woden

Woden is a Teutonic / Norse god that is a derivation somewhere along the line between Wotan, the Teutonic god of War and the more familiar Odin of Norse mythology. His name means “Fury”, and he is still a god of war, but also one of divine inspiration, particularly associated with poetry. Later versions of the god were associated with knowledge and self-sacrifice, and with number symbolism focused on repeating threes and nines.

It’s unclear if he is distinct from those other gods, but a picture of Mary Shelley looking like a more traditional Odin, with an eyepatch and ravens, which are more associated with the later, specifically Norse version of the god. Mary Shelley definitely inspired some poets, so I would guess they’re the same god, and Woden supplies items to the other gods to enhance their abilities. Woden was a name also used by the Norse, so there's probably no Baal-style split here.

The closest musical reference for Woden visually is Daft Punk. Currently we know nothing of who he was before he became a god.

Amaterasu

Shinto is a Japanese religion that predates Buddhism, and was incorporated into Shinto Buddhism when the practice of the newer religion became more common in Japan. Amaterasu is one of the main family of gods, representing the sun - she literally brings light to the world by shining from heaven.

In The Wicked and the Divine, this is reflected in a very optimistic nature. Pre-godly incarnation she was Hazel Greenaway, a teen from Exeter, and she specifically states that she no longer feels that she is this person. This is not necessarily reflected in her actions though - she has a naivety that the other gods don’t that isn’t really in character with the goddess Amaterasu, who is generally wise. In terms of her appearance, Kate Bush is probably the closest touchstone, but she incorporates elements of other musicians too.

Susanoo

Susanoo is Amaterasu’s brother, and the Shinto god of storms. In myth, he frequently antagonises his sister (if throwing a flayed horse at her stuff falls into that category) usually when he is bored. In a core Shinto myth this drives Amaterasu into a cave, thus blocking out the sun. Despite being impetuous and often antagonistic, he is not usually thought of as evil.

He is yet to appear in the modern recurrence, but is briefly shown at the start of the story in the 1920s.

Sakhmet

Again, Sakhmet is a pantheon member that could easily be another god - Bast. The two gods were equivalent in different parts of ancient Egypt, but when the upper and lower Egyptian cultures unified, Sakhmet was the version that was preeminent in the resulting culture, with a cult based in Memphis (the Egyptian one, not the American one, but let’s expect a joke about this at some point).

She is a warrior goddess, who has the aspect of a lioness. She is also the god of menstruation. Her cult was all-female, with daily attendance by her priestesses required to keep her wrath at bay.

The modern-day recurrence version of Sakhmet is heavily influenced by Rihanna in appearance, and is far more animalistic than any of the other gods.

The Morrigan

Well, this one’s fun. The Morrigan is 3 goddesses in one, and with Irish mythology being quite fractured and unreliably-sourced, it’s tricky to dig into the details. They all share the same body, and while this can be true in the source myth, it’s not always the case. She is a shapeshifter, most commonly taking the form of crows, but also an eel and a cow. Her name means “Great Queen” or “Phantom Queen” depending on how you stress the “O”. I told you studying mythology was fun, didn’t I? The Morrigan is not generally portrayed as a chthonic deity (crows being notoriously poor at flying in soil), but she is in The Wicked and the Divine. It might mean something, it might be a good excuse to do a really cool 2-page design that’s mostly black.

The black-haired form is referred to here as Morrigan, but in terms of the myths she more closely resembles Badb (meaning “crow”), who is sometimes considered the primary (and sometimes sole) form of The Morrigan. The Morrigan is always associated with crows, as they were the primary battlefield scavengers. It is this form (more or less - it’s always fun working from fractured sources) that features in the main surviving Irish myth, the Táin Bó Cuailnge. Here she antagonises the hero Cú Chulainn, contributing to his death in battle. This form represents war and death, and while she is primarily a war goddess, she is also associated with death premonitions and death itself (as distinct from people lining up to murder each other).

The red-haired form is called Badb, but more closely resembles Macha, probably Macha red-mane (there are a lot of Macha’s in Irish myth, it gets confusing). This form is probably based on a warlike queen of Ireland who gradually became part of mythology. This form is broadly associated with war, and is the most hot-headed of the three forms.

The third, shaven-headed form is Anu or Anand, who goes by her English name of Gentle Annie (assuming this isn’t Victorian folklorists trying to tie everything into some sort of ur-myth, which they were all over). Anu is not often part of The Morrigan, but it is not unheard of. Anu is not well-represented in surviving Irish texts, but she is generally thought of as a benign mother presence, often symbolising land and sovereignty, which are also symbolised by cattle. This is why the Ulster Cycle of myths is a series of fights over increasingly impressive cows.

Fun fact - there are hills in Munster named after her breasts. In fact the naming of places in ancient Ireland is pretty vulgar for the most part - look it up, it’s a fun afternoon. Start with Fual Meadbha.

I’ll be honest, I struggle to compare these three to existing pop stars, mostly because those people rarely threaten to murder you while screaming about the capacity of their genitals. Maybe Barry Manilow. Gentle Annie definitely has more than a smack of UK comics history about her, with hints of Tank Girl and something Grant Morrison-y in her dialogue. She’s bald, so… Sinead O’Connor? This is what happens when you spend your youth reading about Irish myths, your cultural touchstones drift. I’m sticking with my Tank Girl / Crazy Jane theory.

The Morrigan and Baphomet seem to stay away from the rest of the gods, living in an Underground station while the rest live in Woden’s Valhalla.

Baphomet

Baphomet, like Lucifer, doesn’t quite fit the mould of what we think of as a god - he doesn’t really belong to any religion (unless you’re Aleister Crowley), and he’s never really had worshippers as far as anyone can tell. There is some reference to him as being the god of the Templars, but this is not well supported, and could just as easily be a useful lie from the church of the time to disown the crazy blood-covered people who came stumbling out of the desert years after being sent over. If this is the case then it’s possible that his name was originally a corruption of Mohammed.

References to Baphomet come and go throughout history - in the 19th century he acquired the goat-headed symbolism, equating him with satan worship, and the cult of Thelema (Crowley and chums) adopted him as their own - he was also adopted by the Church of Satan, which is where most contemporary symbolism around Baphomet arises from.

The primary pop reference for Baphomet seems to be Ian Astbury of The Cult, but I don’t remember him having the ol’ washboard abs. Baphomet seems shallower than most of the gods, and this may be related to the fact that he is poorly-understood and has had his symbolism changed quite substantially (broadly invented, really) in the last century. If the gods are affected by human understanding and perception, this would make a certain amount of sense. Of course, he may just have manifested in a daft bastard and stayed that way, although the grinning child star in the opening scenes of the first issue also seems to be Baphomet, and shows the same wilfully destructive nature. This version would predate the Church of Satan, and so I would expect there to be differences between the two versions were this the case.

Baphomet also seems to act as Kieron Gillen’s mouthpiece to an extent - some of jokes seem to be reflexively mocking some of the recurring tropes in Gillen’s work. And then there’s the puns. And “none more goth”.

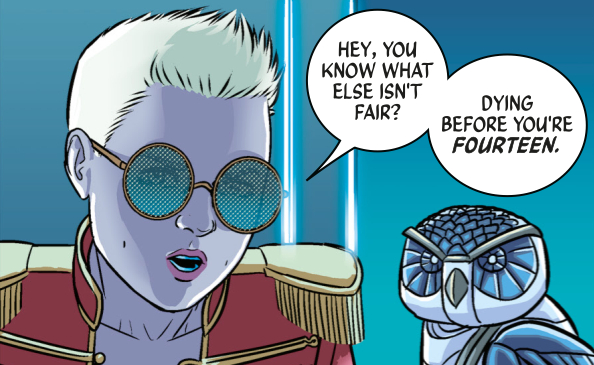

Minerva

Minerva is the Roman goddess of wisdom and the arts, as well as sometimes being a goddess of war (she is the equivalent of Athena in the Greek pantheon). Roman gods frequently had hyperlocalised aspects too, with different towns having their own version of the god. Whether this plays into Minerva’s aspect in The Wicked and the Divine is yet to be seen. She’s not played much of a role so far though, so it’s very hard to tell what her personality is or how her behaviour reflects the god she is. She’s only 12 years old, which seems deeply unfair, but we already saw that the pantheon can be incredibly young in the opening scenes in the 20s.

The militaristic jacket could refer to a whole raft of pop stars, with The Beatles and My Chemical Romance being two obvious ones. Neither of those is a 12-year-old though.

Innana

Innana is the Sumerian goddess of love, fertility and war, and the chief goddess of the Sumerian pantheon. She started as a heavenly spirit, but via a descent into the underworld and experiences symbolic death and rebirth. In some versions of the story, she is forced to exchange places with her lover or husband in order to return, in some she becomes ruler of the underworld, and casts him into it when he takes on other lovers. In most versions she is vengeful on lovers that wrong her.

Innana is the Sumerian goddess of love, fertility and war, and the chief goddess of the Sumerian pantheon. She started as a heavenly spirit, but via a descent into the underworld and experiences symbolic death and rebirth. In some versions of the story, she is forced to exchange places with her lover or husband in order to return, in some she becomes ruler of the underworld, and casts him into it when he takes on other lovers. In most versions she is vengeful on lovers that wrong her.

Innana in The Wicked and the Divine is just Prince. I mean, look at him. Prince. Princey Prince Prince. Which is pretty perfect as a god(dess) of love and fertility. As is the actual Purple Rain that goes with the first appearance of Innana. Of the gods we’ve seen so far, Innana seems to cling to his past more than the rest, and is far more kind than most, and interested in people (or at least Laura, who he was at least familiar with before manifesting as a god.

Tara

We have yet to see Tara in The Wicked and the Divine, but her posters appear everywhere, and the other characters refer to her as being annoying. She is a Tibetan Buddhist deity - “She who delivers”, “star”, and the essence of feminine compassion. She takes 21 different forms, each associated with a different colour, posture, and temperament - this seems to equate to Lady Gaga-esque costume changes in The Wicked and the Divine, but it’s yet to be seen. Certainly the only image of her that we’ve seen so far is very colourful - blue, which is one of Tara’s furious forms. Green and white forms are loving.

(This post covers roughly issues #1-7. The rest of the gods are covered in part 2 here.)

Performed Identity in The Wicked and the Divine

Or: Roger wanks on a bit about gods.

The gods in WicDiv are pop stars, but the nature of the medium makes it impossible for us to hear them sing. What, then, do they do, and what are they? When they perform miracles - or their heads explode - the pages fill with halftones, and the medium rushes in. They are gods in a story, performers, and neither we nor they get to forget that. The book is so coyly, posedly, not “about the music” that this sharply underscores the gods’ function as a different kind of performer. They’re the pure froth of pop, performing the identity of the star.

Each of these gods have multi-part identities. There’s the mythological god they represent, the human they were, and the pop star they act as. So far, most of the other characters with speaking parts have something similar going on, too. We meet Laura as she’s dressing up, and the fandom she enacts involves shifting her appearance for each of the gods. She explicitly dresses as Amaterasu, she nods to Lucifer’s outfit for her prison visit, goes all goth gothy goth goth for the Morrigan, and well, I've got nothing on the dungarees; art student for the gallery, maybe. She glosses over her family life, the ordinary teenager she was, by showing it to us through the ironic detachment of the narrator/protagonist she’s busy being.

Her narrator voice itself is not uncomplicated. It has distance and perspective, sometimes in the moment, sometimes relating a story from the past. It has flashes of self-awareness, (“fail girl”, “desperation”, the family argument she breezily voices over) but they serve the pose. There are at least three bits of identity here, too. Laura plays a lot of roles, then. But they’re more tentative and experimental than the performances of the gods.

She occupies a mid point along WicDiv's sliding scale of identity performance. The gods sit at the high-end, an iconic expression of teenage theatrical self-creation. At the other and we have every other teenager, and the teenagers the gods were before. In between: Laura. She wants what they have, to an extent, and in a slightly try-hard way. Heck, she’s trying amazingly hard to be an iconic teenager. Failing her A-levels is “a statement of intent”. The posed cool at Valhalla is achingly fragile, and of course she knows that, it’s the joke. Dressing as Amaterasu, she literally (cos)plays in a toilet while the gods gig in stadiums.

Laura’s not quite our everyman, her status as probably-narrator complicates that. She’s finding her feet playing a role, performing bits of what the gods do, bits of something else. Interestingly (and I’ll love seeing where this goes) she’s got a lot more agency than the gods do. Narrating alone gives her some of that, setting the terms on which we can engage with the story. But she’s got a bit more freedom in it too. There are plenty of performers, but not that many actors - the gods largely react, or inspire, or follow their stories.

Cassandra looks initially to have a simpler identity. Superficially more of an adult, she’s cast as the sceptic. But the background in comparative mythology and her disappointment at what she feels the gods are not suggests a kind of fandom and infatuation. She plays, too, with being the mythic Cassandra. It’s not overdone, but the gods are dismissive of her, and she’s clearly had to fight for her voice.

Then of course, there’s the pointed, casual, almost unforeshadowed trans reveal. It’s an odd beat. It feels initially on the nose, but then conspicuous for being throwaway. It would have been easy to use a trans character as a cipher for the identity concepts, to dwell on an early life spent obliged to perform a wrong identity, perhaps. This would play to the book’s analysis of teen experience, and maybe it does suggest that a little. From what we see of Luci's past as “Ms Rigby”, from Cassandra’s faint dismissal of Amaterasu as a provincial girl, from the snatches of Laura’s life, and her wishing for godhood, cosplaying in front of a toilet, we get a strong waft of that feeling of (musical?) subculture as teenage escape.

But it still feels like more of a character moment for Lucifer. It’s a moment of casual cruelty, tossed out as a barb. The apology for outing is itself an outing, and a much more conspicuous one than anything before. The “lord of the pit”, bloodied, the hurt child showing through, is maybe trying to prove she’s still got it? It’s a moment between her and Cassandra, and the narrative broadly shrugs it off. The nonchalance feels progressive, but there’s also a playfulness. A nod and a wink that says, here, have this one, we've got identity tropes to burn. The book is more interested in the performed, multi-part identity of every teenager, and the caricature expressed by the gods, than in cruelly fetishizing one transition.

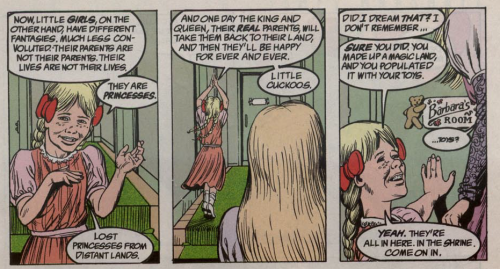

The gods, then, are a bit of an expression of the teenage experience, of wanting to be special and lifted out of your life. In A Game of You, Neil Gaiman has The Cuckoo talk, almost direct to the reader, about childhood fantasy:

She breaks it out along questionably gender-essentialist lines as agency fantasy for boys, identity for girls: “Their parents are not their parents. Their lives are not their lives.” Let’s ditch the genitals and generalise – the gods of WicDiv are a kind of synthesis. Being plucked from (miserable) childhood obscurity and told by a terrifying caricature grandma that you’re a god? It’s the height of identity and agency fantasy; it’s what(ever) happened to the teenage dream.

But it’s not the end-point, and the teaser for the book clearly set out the premise “just because you’re immortal doesn't mean you're going to live forever”. Amaterasu clarifies “You spend your entire life wishing you were special and then find out you are. Nothing is without a price.”

Clearly, the book is at least in part about haggling over that price. Faustus and the Vengaboys tell us that on the flyleaf. But there’s a degree of haggling over “special”, too.

There’s a great blog post called How an Algorithm Feels From The Inside (and this related piece) that has a lot to say about the cognitive fluency of categories, and by implication the persistence of pathological essentialism. Which is to say “are they really gods?” may just be another “but is it art?”, and broadly not helpful in the face of duck typing. But in a piece that tosses around specific niche versions of Baal - versions in which Baal himself is invested - I’m not so sure. Mythopoetically, Lucifer and Baphomet are younger than the others as gods/whatever, and have a touch more naïve brattishness. If these are Gaimanesque gods as empowered by human belief, then their role as inspiration becomes kind of oddly recursive, and whether they are “really” gods is relatively important. The presence of Lucifer amidst a pantheon drawn extensively from polytheistic faiths would invite us to ask questions about the presence or absence of monotheism’s beardy sky-ghost, whichever way you slice it. The extent to which they’re “gods”, what that even means, and their relationship to their own and each other’s mythology is very much front and centre, so maybe we’re interrogating the category.

There’s a great blog post called How an Algorithm Feels From The Inside (and this related piece) that has a lot to say about the cognitive fluency of categories, and by implication the persistence of pathological essentialism. Which is to say “are they really gods?” may just be another “but is it art?”, and broadly not helpful in the face of duck typing. But in a piece that tosses around specific niche versions of Baal - versions in which Baal himself is invested - I’m not so sure. Mythopoetically, Lucifer and Baphomet are younger than the others as gods/whatever, and have a touch more naïve brattishness. If these are Gaimanesque gods as empowered by human belief, then their role as inspiration becomes kind of oddly recursive, and whether they are “really” gods is relatively important. The presence of Lucifer amidst a pantheon drawn extensively from polytheistic faiths would invite us to ask questions about the presence or absence of monotheism’s beardy sky-ghost, whichever way you slice it. The extent to which they’re “gods”, what that even means, and their relationship to their own and each other’s mythology is very much front and centre, so maybe we’re interrogating the category.

They’re tightly bound by rules, “don’t really do anything useful”, and quite apart from the fact that they've only got two years to live, seem at least partly shackled to a narrative imperative they can make jokes about but not fight.

Lucifer chuckles about what a story it would be if Innana were the killer, that “genre tropes dictate” it was likely Amaterasu, or the “twist” if it were her herself. But for all this, she still ends up enacting a little bit of the Lucifer story – favoured, rebelling, punished. She spends a chunk of the story in a prison cell for transgression, and yet still sees Ananke as caring for her, giving “the best advice”. Sakhmet plays at cat, and the laser pointer is a delight. Laura points at the theatricality of the “play” between Baphomet and the Morrigan. It’s part the self-destructive myth of the pop star, and part the story of the god, rolling out regardless. No wonder Luci is quite so pissed off.

Lucifer chuckles about what a story it would be if Innana were the killer, that “genre tropes dictate” it was likely Amaterasu, or the “twist” if it were her herself. But for all this, she still ends up enacting a little bit of the Lucifer story – favoured, rebelling, punished. She spends a chunk of the story in a prison cell for transgression, and yet still sees Ananke as caring for her, giving “the best advice”. Sakhmet plays at cat, and the laser pointer is a delight. Laura points at the theatricality of the “play” between Baphomet and the Morrigan. It’s part the self-destructive myth of the pop star, and part the story of the god, rolling out regardless. No wonder Luci is quite so pissed off.

WicDiv is a long way from being finished, but it’s already got a lot to say about how we create and perform identities, and about what that performance enforces. It’s full of little jokes and tragic ironies, and it’s a delight for inviting us to play guessing games. I’ve not even touched on the micro narratives it packs into the gods’ icons, and what roles the gods might play in determining the iconic character of their eras. There are shivers of this in issue six, and teasers about “missing pantheons”. There’s a rich seam of glib comparisons to Phonogram to mine, too, and some less fatuous notes about perspectives on youth experience, growing up, and constraints of agency, especially relative to Young Avengers. We might return to that as WicDiv unfolds.

(If you like a bit of people close-reading themselves as they go, Kieron Gillen often posts writer’s notes on his blog They’ll tell you more than I could about what’s going on, and with a good deal less hand waving.)