Now, I can't promise that if you watched King of the Hill after dropping acid it would look exactly like Cowboys and Insects. But those already familiar with Shaky Kane's style and the amped-up pulp vibe he created with David Hine in The Bulletproof Coffin would likely find the experience quite familiar.

With its giant bugs, bright colours, ranch hands with rifles, and a sickly uncoiling of fifties American paranoia, Cowboys and Insects is a lurid thing that takes us to a pretty severe place.

Childhood wonder to lynch mob in twenty pages, each step feeling natural and normal, and not worthy of moral scrutiny.

First published digitally in 2013, when it wasn't a given that white America would plump for fascism in a fit of butthurt cultural pique, Cowboys and Insects seems oddly prescient now.

Much of its effect, I think comes not from being on-the-nose preachy, but rather from running full-tilt at the joyous daftness of the premise and letting that carry it through.

(The spoiler-averse may wish to stop here; also folks who don't like gross stuff with insects)

Cowboys and Insects blends a frog-boil to the monstrous with a red herring around just what the monster is. Giant bugs are a B-movie staple, and so is the idea that the real monster is man. But the book does a sensational job of splashing around in the weirdness of gargantuan beetles while also selling us on a world where they're quite, quite normal.

It's full-on Uncanny. Something like a housefly, turkey-sized, gracing a roast dinner platter, nuclear family all gung-ho to tuck in. Mom in meat-packing plant, tossing slime-slick larvae off a conveyor belt, squealing sound effect at the bottom of the panel, half-cocked job-well-done smile on her face at the top:

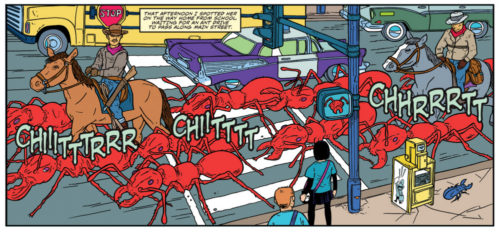

A cattle drive of giant ants down a fifties street of cadillac tailfins.

All through, it's sold by Chip's voice. We're watching through his eyes, but we can't escape our own. It's normal. It's fantastical. It's just a memory from highschool of the first girl he had a crush on. It's a gut-churning hate crime, perpetrated without pause or conscience.

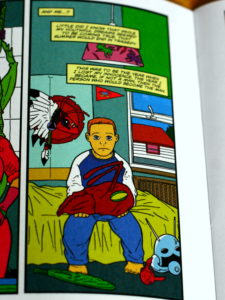

This kind of voice-of-the-child deal can be easily overused. Much of the power of Barefoot Gen lies in showing us something that attempts to be a normal childhood while the world around it counts down to eight fifteen. It could be clumsy. It isn't, and part of what does that work is the visual style - breezy and casual in just the right places - part of it is how well realized the childhood voice is.

The styles are very different, but the same applies here. Art and voice, selling this vibrant pulp adventure adolescence.

Chip moves to a new town with his folks. Bug Town, Colorado - a ranching monoculture for the fifties economic boom. He finds a new school meets people, enjoys the scents and sights of a giant stag beetle rodeo. It's golden-age teen memory stuff, all worked through with these perfect vignettes in flat simple colours that make this sci-fi scenario seem like workaday picket fence stuff.

Chip moves to a new town with his folks. Bug Town, Colorado - a ranching monoculture for the fifties economic boom. He finds a new school meets people, enjoys the scents and sights of a giant stag beetle rodeo. It's golden-age teen memory stuff, all worked through with these perfect vignettes in flat simple colours that make this sci-fi scenario seem like workaday picket fence stuff.

We're told this as memory, coming of age style, just a little Stand By Me:

This was to be the year when I lost my innocence. The year I became if not a man then the person who would become the man.

The definite article feels salient there. "The man". Performance of duty and enforcement of white bread normalcy become key, but we're walked through it with this tone that never slips - Chip's conviction that this is the world, that daddy knows best, and that this is all part and parcel of growing up into a right thinking adult.

The definite article feels salient there. "The man". Performance of duty and enforcement of white bread normalcy become key, but we're walked through it with this tone that never slips - Chip's conviction that this is the world, that daddy knows best, and that this is all part and parcel of growing up into a right thinking adult.

"It's not always easy to choose between right and wrong" he remembers thinking, sat in his bedroom, sad and anguished about a girl he's fallen for, choosing a path that ends with her being eaten alive by burrowing beetles.

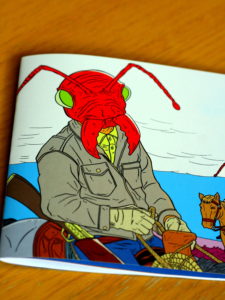

Again, it feels natural. We move through this experience with him, exploring this strange world as he does. The strangeness of it is never far away - there's hardly a panel without some kind of giant insect detail or oddity. It's remarkable to us, but only remarkable to Chip as a new experience in a familiar world. There's some wonderful cake-and-eat it there with breaking the suspension of disbelief. Chip's excitement at getting to dissect a giant bug, the oddly human-seeming Insectum Erectus, lets us feel the strangeness without coming up for air.

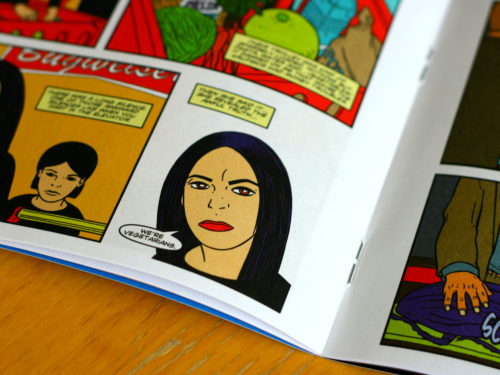

At his new school, busily dissecting bugs and learning about their place in modern agribusiness, Chip meets Cindy Krupski. Her family are shown more pale, dressed severely, and often in black. It's not subtle othering, but played against the cartoon colouring it's a great sell for their terrible secret:

Cindy doesn't fit in. Chip is infatuated. Cindy certainly doesn't want to dissect a novel species of insect that's shown visibly afraid, walking upright, and - entirely unremarked - wearing a loincloth.

Chip doesn't get it.

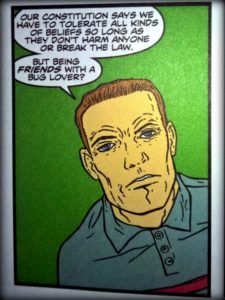

Chip asks his dad for advice.

Chip has the narrative framed for him in terms that echo miscegenation.

The Krupskis are the only dissenting voice in Chip's world, and their behaviour is so strongly framed as deviant, as a danger, that as readers we're not incredulous for a moment that Chip might not pause to interrogate his circumstances. We're watching what inculcation into systemic and structural prejudice feels like from the inside, and by the end I felt almost nauseously complicit.

The Krupskis are the only dissenting voice in Chip's world, and their behaviour is so strongly framed as deviant, as a danger, that as readers we're not incredulous for a moment that Chip might not pause to interrogate his circumstances. We're watching what inculcation into systemic and structural prejudice feels like from the inside, and by the end I felt almost nauseously complicit.

What an ending, too. Things escalate pretty fast, as Chip confides in his father that the Krupskis are sheltering the escaped bug, and the town isn't happy.

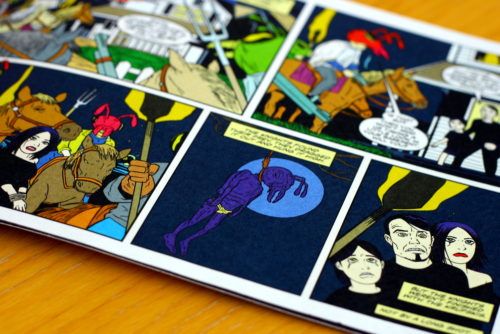

The Knights of the Head are a legendary brotherhood of men who stalk the night, seeking out those who transgress the boundaries between man and insect.

Yes, they wear masks made from hollowed-out insect heads. Yes, they have robes like klansmen. Yes, it goes very, very badly.

That panel. The simple geometrics and the limp dangling. The loincloth. It doesn't even stop there.

As we reach the conclusion, there's a slight shift in Chip's voice, something febrile and excited by the moment, with a storyteller's feel ("But the knights weren't finished with the Krupskis, not by a long shot..."), moving to a factual acceptance. By the end, they're "the wretched Krupskis", and Chip has pulled forward to being the adult narrator more cleanly: "...I've become something of an expert on the Necrophorous Vespillo over the years".

His childhood excitement is still there, as he related the lifecycle of the burrowing beetles, but it's distant, more future factual.

It's interlaced, too with a new panel structure, big bordering gutters against black, tall vertical panels where the book's tended to the horizontally sequential. It suggests a series of snapshots, memories perhaps, but more fractured:

What's remembered is monstrous, the beetles are finally horror movie schlock. The vertical feel is almost like drowning - insects and their sounds rising from the bottom of the panels to horrified faces compressed at the tops.

Imagine that - alive for a month or more under the ground, with insect larvae growing inside you.

His tone doesn't judge. Is it horrified, or just showing his amateur-entomologist glee? It doesn't commit.

Why would it - this is his normal now. It's "They way we raise 'em here in Colorado", and nobody in the town bats an eyelid. Chip's a grown man, and only remembers when he catches a flash of something, perhaps on TV, and for all the thin whisper of guilt on the page before, it's still a memory of the first girl he kissed.

The iconography cribs from southern racism, but the book offers a highly transferrable view inside the machineries of group supremacy, identity policing, and structural power.

This doesn't feel like a period where we have to look far for the horrific becoming ideologically mundane. It's not a great world to be any kind of Other in, and the scope for that getting better seems scant. In playing so neatly with normalization, and with what does and does not seem extraordinary, in rendering it all in this kitschy/pulpy growing-up caper, the print edition of Cowboys and Insects feels timely and urgent.

(We briefly interviewed David Hine about the book at Thought Bubble, and it's on the podcast)