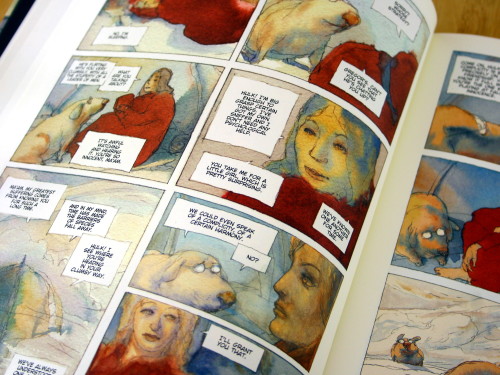

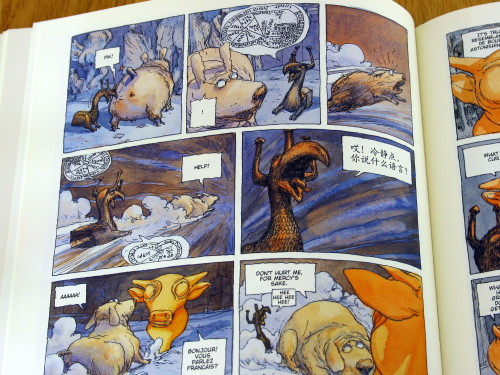

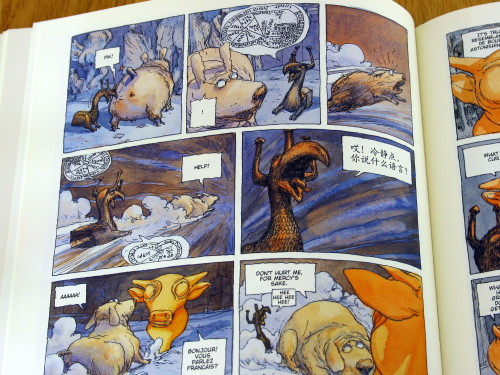

This faux-historical gloss is mirrored later by the paintings' own experience as they come to life and tell their story. This is softer, more ordered as narrative, and resting on impressionism. There are little bites taken out of a lot of styles in this book, and even within the period of the narrative, it meanders between watercolour, fidgety linework, and something bolder like gouache. It's fitting that in a piece that has the front to use big-ticket Masterpieces as throwaway panels, so many of its original panels should be arrestingly beautiful.

There's a tendentious reading there that I can't quite make stick: that the sections outside the gallery more strongly replicate for the reader the experience of viewing visual art (in a gallery) than the exhibition pieces themselves.

Running with that briefly, you could hold up the foregrounding of the paper stock and brushstrokes, the shifting overtly-painted styles, next to the incredibly casual use of renaissance paintings, and the way in the second half the massed artefacts become indistinct.

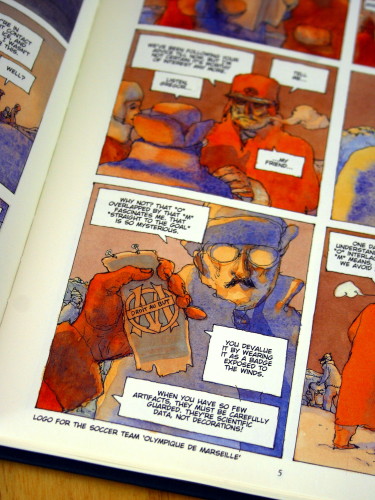

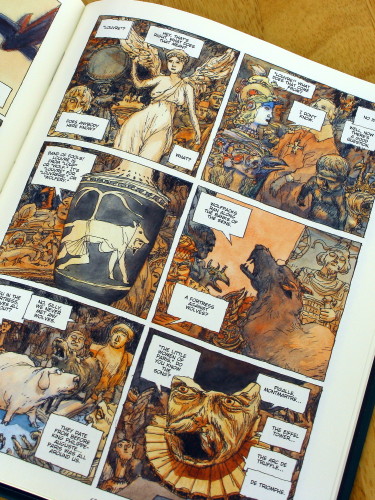

I'm not wholly sure you can sell that. It's hard for most bets not to be off once Hulk encounters the museum pieces talking. But I do think it's at least in part about how we read and experience museums and art. Worthiness isn't privileged, and there's a kind of set of wry jokes here about curation and experience.

Hulk's nose gives him a chronology, but it doesn't stop him making mistakes. Joseph seeks a narrative from the images, collaging a comic on the fly. We the readers may or may not know that the art styles he chooses don't go in that order, but the very fact that the joke doesn't depend on that knowledge means we don't get to be smug if we have it, or get to take that much comfort in context.

Nobody gets to be right except the exhibits themselves, and they aren't wholly reliable narrators. The only fact-checking is the reader's (arbitrary) level of knowledge. It's a wonderful model of coming to a vast collection and negotiating how and how much to trust the interpretation on offer.

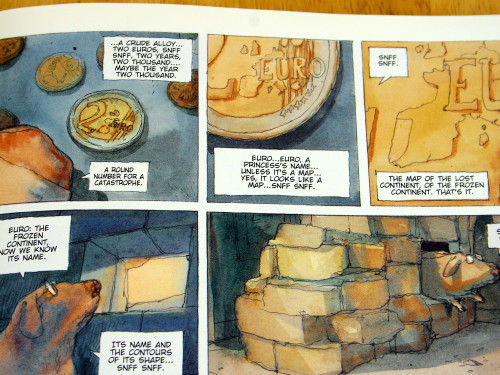

Indeed, Glacial Period shows us two ways of reading museums, almost two experiences of curation. It's not quite this clean; the book doesn't harangue us about how to experience art. But it does face off a more proscriptive, historicist approach with something looser, more serendipitous and imaginative.

It's a trip to a museum, after all, howbeit a weird one. The premise aggressively strips back and context or expertise the characters might arrive with, so they're left with only their inclinations and approaches. Gregor has consistently been dogmatic and patriarchic. Paul has fared a little better but constantly asserts his credentials as historian while knowing little of history. The others have been more open. Joseph tells the centrepiece story, but tweaks it on the fly - there's a joy and eagerness in his attempt to interpret. Juliette balances hypotheses, and Hulk for all his precociousness asks more often than he asserts. The collection quite literally comes to life before him, and he teases out the history of the place by conversing with the artefacts.

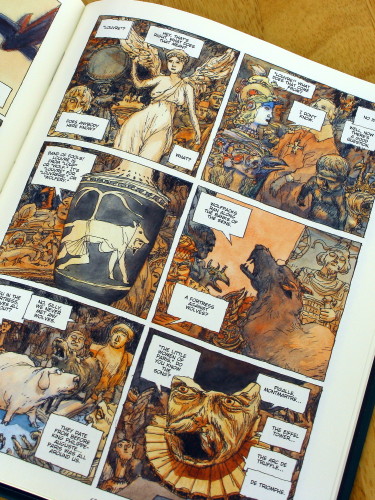

As the book ends, Gregor is a puddle on the floor, and Paul watches quietly dumbfounded as Hulk, Juliette, and Joseph gallop off on the back of an aggressively postmodern collage in the rough form of Anubis, "a new work freed from its jewelry box."

I guess the moral of the story is that if you approach museums with flexibility, openness, and a sense of wonder, you get to ride out into a bold new life on a transcendental post-structuralist magic art dog, whereas if you're all po-faced and strict about it you get eaten by an angry beef monster?

I don't know - it goes off the rails pretty hard at the end there, but I defy you not to love it for that.

I've taken a pretty strong position here on what it's doing, but there's a lot more in Glacial Period. It's a history of the Louvre, an examination of how art means, and an amazing sketchbook. It's big and weird and utterly, utterly beautiful.