Aama is one of the books I picked up on the ConSequential jaunt to Thought Bubble this year, and it's tremendous fun. It's Big Weird Sci-Fi of the kind we talked about on the podcast, heavily influenced by Mœbius, and drawn like something Tintin hallucinated. Although personally, I think it takes The Incal to the cleaners.

There are - I think - three volumes of Aama currently available to those who can read well enough in French. Since that doesn't include me, I'm stuck with the first volume only: The Smell of Warm Dust. It was first published in English at the beginning of November, by the lovely Self Made Hero. Please buy it - I want the numbers to look good enough that they translate and publish the rest.

Aama has some of that grand-yet-baffling visual sweep of Brandon Graham's Prophet, but it's far more human and intimate. Heck, it starts with a single face; and ordinary man, face down in the dirt.

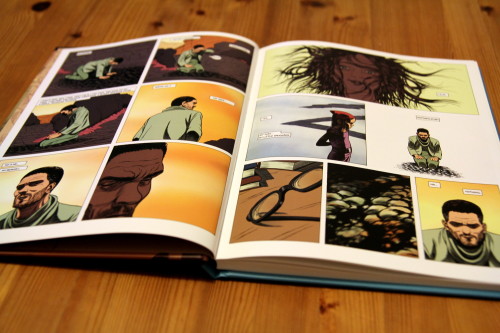

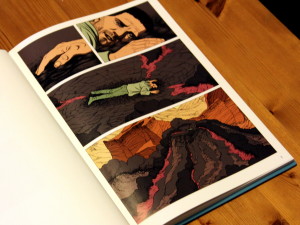

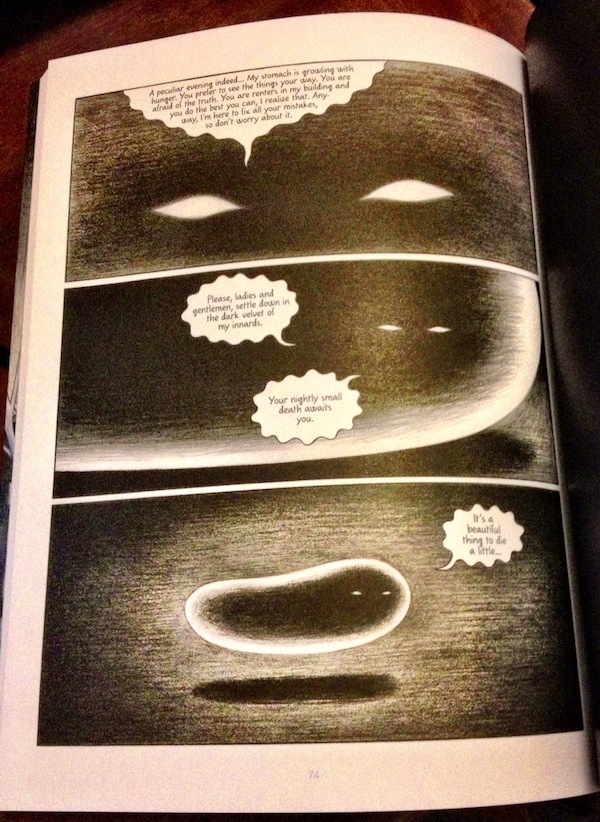

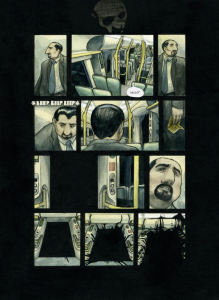

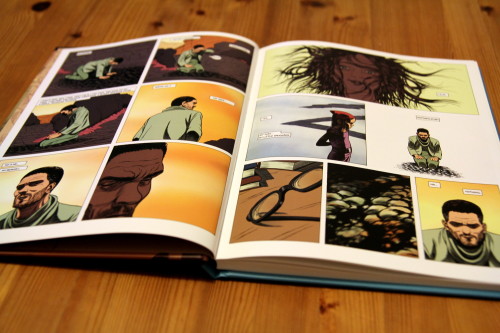

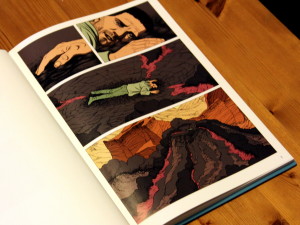

You turn through from its Big Weird Sci-Fi cover, cigar-smoking robo-chimp and all, to something so very close - completely scoped to one man. The panels lengthen and expand with the visual sweep. It begins with a hand, tight, clear detail to the front of the panel, moving out to an emptier background, controlling focus and scale like a classic Dali landscape. The next, twice the size, is a face, flat on the earth and weeping. The final two panels of the page, larger, then larger again, are full-width strips, expanding back to show the man in a crater, and the crater in an odd, but not yet wholly-fantastical landscape.

You turn through from its Big Weird Sci-Fi cover, cigar-smoking robo-chimp and all, to something so very close - completely scoped to one man. The panels lengthen and expand with the visual sweep. It begins with a hand, tight, clear detail to the front of the panel, moving out to an emptier background, controlling focus and scale like a classic Dali landscape. The next, twice the size, is a face, flat on the earth and weeping. The final two panels of the page, larger, then larger again, are full-width strips, expanding back to show the man in a crater, and the crater in an odd, but not yet wholly-fantastical landscape.

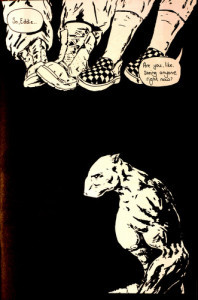

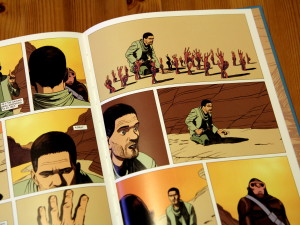

I'm not going to take the whole book frame by frame. But from here it pulls out more, tracked close on the man - Verloc Nim - as he composes himself and takes in his surroundings. It's a full five pages before he rises to his feet, aided up by a creature with the torso of a gorilla and the legs of a scrawny man, and the oddity of the world comes breaking in. Nim's memory is vague, amnesiac, and his body is unfamiliar to him. Once near-sighted he has perfect vision. The gorilla/robot introduces itself as Churchill, and hands Verloc his diary, encouraging him to read it as they make their way back to "the colony".

So begins a moderately conventional memory/self-recovery narrative, with an emerging past intertwined with an exploratory present. Verloc walks across this alien dessert while showing us the past that will eventually lead us to it.

Here, if it hasn't already, is where a double-headed penny drops. On one side, the rough outline of Joseph Conrad's Adolf Verloc, on the other, Alejandro Jodorowsky's John DiFool.

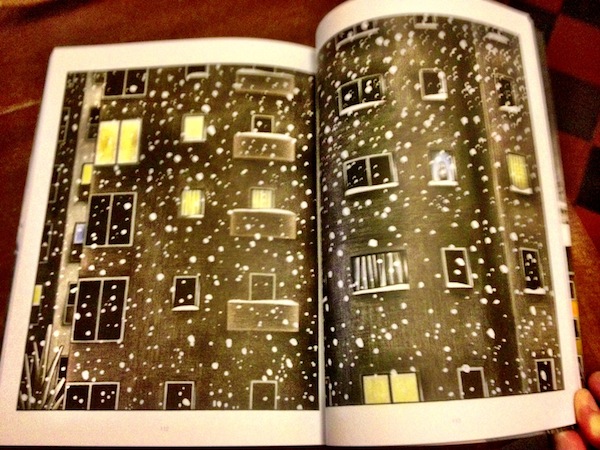

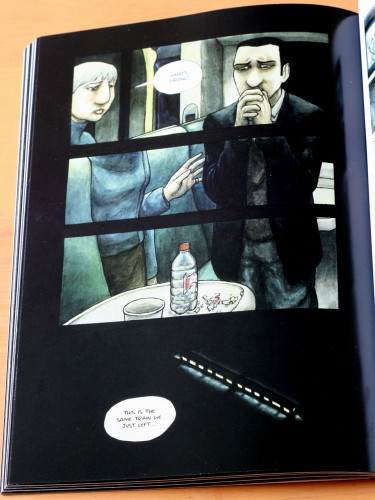

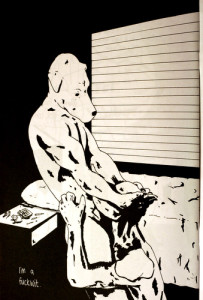

Like both, Veroc Nim is a kind of feckless down-and-out hero refusenik. The narrative of his past begins with him also face down, stoned out of his mind in puddles of his own filth on the lowest levels of a towering future megacity. The shades of The Incal's setting are fairly clear. There's both early narrative and traits in common here with DiFool. Although with mercifully fewer cack-handed tarot references. Like Conrad's Verloc, too, he's a dealer of books and bric-a-brac in the seedy side of town, and a fidgety indolent; unable - quite - to lift himself out of his malaise or circumstances.

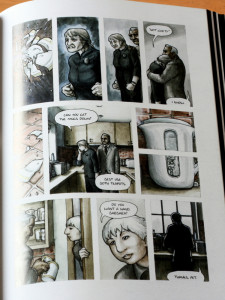

In this Veloc's case, that malaise is an epic drug bender that began after losing his livelihood to a confidence trickster, and his wife and child soon thereafter. He's rescued, without explanation, and by seeming coincidence, by his estranged brother - a kind of corporate fixer and gun for hire, in the pay of a shady megacorp we soon discover to be responsible for much of the decay and destitution Peeters draws around them.

Peeters has also come right out and called the brother "Conrad". I'm just going to leave that there, along with some vague allusions about authorship and creation (indeed, Conrad physically modifies Verloc as the story progresses), and then point out that it's still less painful than "DiFool".

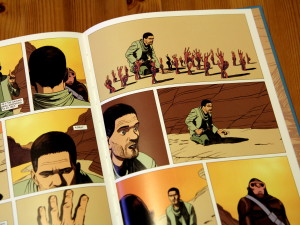

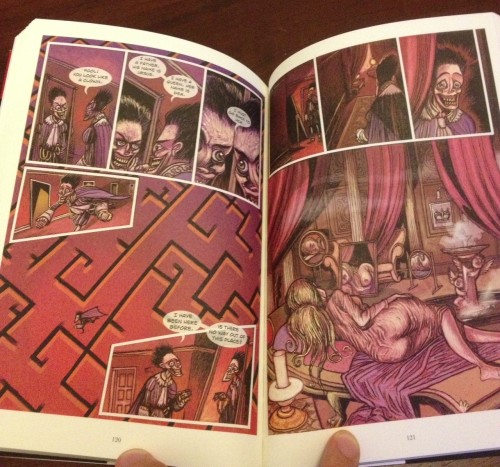

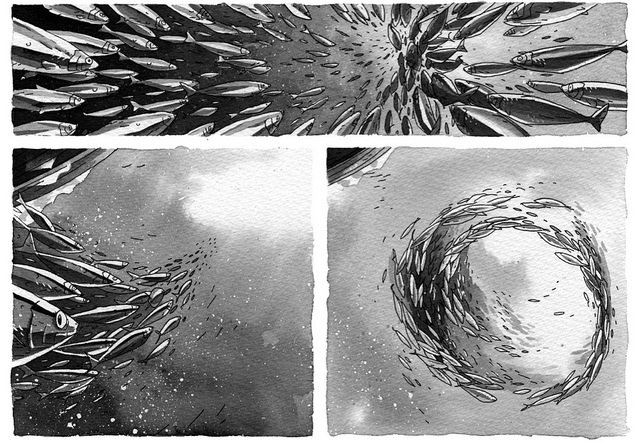

Together, the brothers embark on a mission to find a lost colony. It's one of the corporation's experimental outposts, home to some kind of nascent indistinguishable-from-magic biotech, from before the "Great Crisis" six years ago, when contact was lost. As they travel, Verloc recounts more of his past, and we see some gorgeously crazy and abstracted world design around them - spiky geometric spaceships, odd little bubble cars, slums full of mutants, and drug dens in dense, oppressive deep hues. Peeters' colouring does a lot of heavy lifting here. Each locale has a palette, with the range of colour expanding and compressing with the mood and tone of the action. The city is blues and purples, oppressive and close. The colony landscapes are expansive, higher contrast greens, browns, and yellows, with the colony outpost in claustrophobic reds.

Together, the brothers embark on a mission to find a lost colony. It's one of the corporation's experimental outposts, home to some kind of nascent indistinguishable-from-magic biotech, from before the "Great Crisis" six years ago, when contact was lost. As they travel, Verloc recounts more of his past, and we see some gorgeously crazy and abstracted world design around them - spiky geometric spaceships, odd little bubble cars, slums full of mutants, and drug dens in dense, oppressive deep hues. Peeters' colouring does a lot of heavy lifting here. Each locale has a palette, with the range of colour expanding and compressing with the mood and tone of the action. The city is blues and purples, oppressive and close. The colony landscapes are expansive, higher contrast greens, browns, and yellows, with the colony outpost in claustrophobic reds.

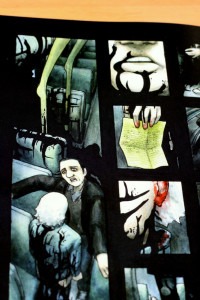

The panel flow and guttering, too, remains regimented in the most part. It slices out time, until suddenly it will pull in tight on a person - a face or gesture, sometimes outside the main panel structure, for moments of emphasis or extreme emotional reaction.

In a few moments of extreme action, the guttering becomes slanted, the panels more weirdly geometric, mimicking either motion lines or a sense of general chaos. So when Churchill fights one of the colony's rogue robots, the otherwise highly regular, measured structure fractures into something far more kinetic.

The colony itself is a mystery. It's key scientist, Woland, has absconded, and taken her discovery ("aama") with her. By scant implication, aama is some kind of mystical possibly-terraforming nano-goo. This could easily all go a bit Star Trek II. As Verloc and Conrad bicker with the remaining faction, a child strolls in. Mute, and identical to Verloc's estranged daughter Lilja, she appeared without explanation, a week before.

Nods to The Incal's Solune are there, but without all the incoherent yelling about hermaphrodites. Aama teases us with an actual puzzle, rather than mere bad writing.

As the first volume ends, the Verloc in the present is walking back to the colony from who knows where. His memory is in tatters, and he's beginning to believe he can feel the landscape try to speak to him. The Verloc in the diary he's reading to us is about to set out into that dessert to pick at some of these mysteries. The colony is degenerating into a tiny cult, and the outpost is under siege from its own robots.

As the first volume ends, the Verloc in the present is walking back to the colony from who knows where. His memory is in tatters, and he's beginning to believe he can feel the landscape try to speak to him. The Verloc in the diary he's reading to us is about to set out into that dessert to pick at some of these mysteries. The colony is degenerating into a tiny cult, and the outpost is under siege from its own robots.

It's weird and it's intriguing. The characters' motivations are hazy, as is the structure of just what is going on. But unlike The Incal, this has a feeling of definite construction. It smacks of something coherent playing out, rather than of being written, tone-deaf, from one panel to the next. It looks like Mœbius' mad sci-fi world, for sure, and there are enormous parallels of structure and character. The colouring and landscape design are even similar.

But there's a clue to the difference, I think, in just how many of Aama's panels focus keenly on Verloc's face, and how expressive it makes his eyes. This is full of actual people who seem to feel things.

It's also full of effects that follow on from coherent causes, which Jodorowsky really wasn't so hot on.

I don't know what's going to happen to Verloc Nim - the persistent, gently tragic thwarting of Adolf Verloc, the gender-bending nonsensical back-seat apotheosis of John DiFool, or something else entirely. There are plenty of tropes Aama could lean on, and it's wide open to play games with the reliability of its narrator and its reality. Quite apart from being beautiful, it's going to be enormous fun finding out.

Blue is a librarian, a genre / pulp specialist whose obsessive cataloguing of old stories drove him apart from his wife, leaving him ready to die. His awareness of genre is key to the tale, as Spurrier takes the opportunity to berate him, and by implication the reader, for importing pulp and Western tropes to the story that is, after all, just about a sandy frontier full of settlers, warring factions and treachery. Story - Spurrier's Story, possibly all stories - is far too important to leave to lazy clichés to fill in. There's a fantastic scene where Blue "wins" - for an incredibly simplistic version of winning. Bad guys are killed, Blue is left rich, but as perspective draws further and further back, leaving him a speck, he realises how empty this matinee-movie ending is.

Blue is a librarian, a genre / pulp specialist whose obsessive cataloguing of old stories drove him apart from his wife, leaving him ready to die. His awareness of genre is key to the tale, as Spurrier takes the opportunity to berate him, and by implication the reader, for importing pulp and Western tropes to the story that is, after all, just about a sandy frontier full of settlers, warring factions and treachery. Story - Spurrier's Story, possibly all stories - is far too important to leave to lazy clichés to fill in. There's a fantastic scene where Blue "wins" - for an incredibly simplistic version of winning. Bad guys are killed, Blue is left rich, but as perspective draws further and further back, leaving him a speck, he realises how empty this matinee-movie ending is.